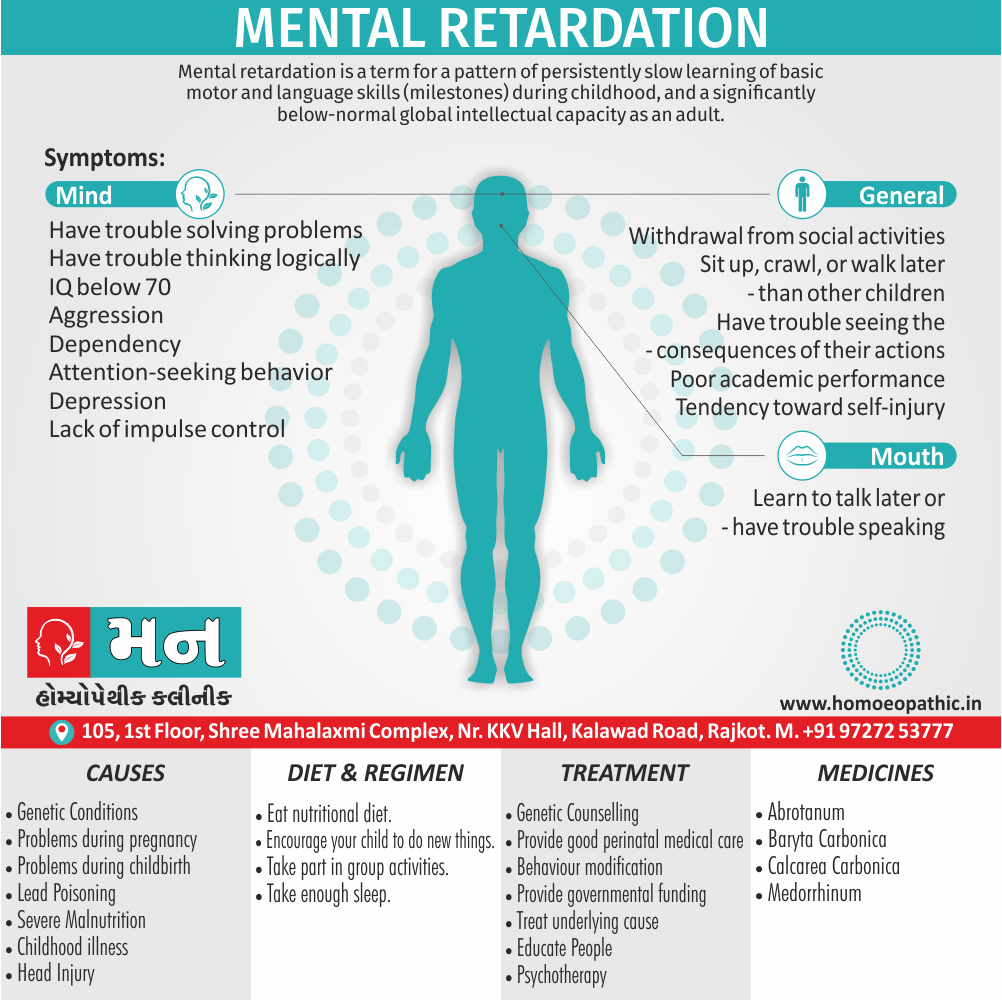

Mental Retardation

Definition

Mental retardation is a term for a pattern of persistently slow learning of basic motor and language skills (milestones) during childhood, and a significantly below-normal global intellectual capacity as an adult. [2]

Mental retardation is defined as significantly sub average general intellectual functioning, associated with significant deficit or impairment in adaptive functioning, which manifests during the developmental period (before 18 years of age). [1]

The term "mental retardation" is considered outdated and can be insensitive. Here are some respectful alternatives you can use:

Formal:

- Intellectual disability (ID): This is the preferred term by many organizations and emphasizes the challenges faced with cognitive functioning.

- Cognitive impairment: This is a broader term that refers to difficulties with thinking, learning, and memory, but doesn’t specify the severity.

Neutral:

- Developmental disability: This term refers to a group of conditions that start early in life and cause delays in development.

It’s important to choose the term that best suits the context. If you’re unsure, "intellectual disability" is a safe and widely accepted option.

Overview

Epidemiology

Causes

Risk Factors

Pathogenesis

Pathophysiology

Types

Clinical Features

Sign & Symptoms

Clinical Examination

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Complications

Investigations

Treatment

Prevention

Homeopathic Treatment

Diet & Regimen

Do’s and Don'ts

Terminology

References

Also Search As

Overview

Overview of Mental Retardation

Generally, One common criteria for diagnosis of mental retardation is a tested intelligence quotient (IQ) of 70 or below and deficits in adaptive functioning.

Moreover, People with mental retardation may be described as having developmental disabilities, global developmental delay, or learning difficulties. [2]

All in all, General intellectual functioning is usually assessed on a standardised intelligence test with significantly sub average intelligence as two standard deviations below the mean (usually an IQ of below 70), whilst adaptive behaviour is the person’s ability to meet responsibilities of social, personal, occupational and interpersonal areas of life, appropriate to age, sociocultural also educational background. [1]

Adaptive behaviors:

These are skills necessary for day-to-day life, such as being able to communicate effectively, interact with others, and take care of oneself.

Adaptive behaviour is measured by clinical interview and standardised assessment scales.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology of Mental Retardation

There are a few references on the epidemiology of intellectual disability (ID) in India:

- Prevalence of intellectual disability in India: A meta-analysis (2022) suggests that the burden due to ID is only third to depressive disorders and anxiety disorders in India. This national burden significantly contributes to the global burden of ID. The study aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of ID in India and examine the sources of heterogeneity across the included studies.[4]

- National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: This survey provides comprehensive information on the prevalence of various mental disorders in India, including intellectual disability. It also covers the patterns and outcomes associated with these disorders.[5]

- (PDF) Intellectual Disability in India: An overview: This overview discusses the challenges and opportunities related to intellectual disability in India. It highlights the need for better identification, assessment, and intervention services for individuals with ID.[6]

- (PDF) Prevalence of mental retardation in urban and rural populations of the goiter zone in Northwest India: This study focuses on the prevalence of mental retardation (an older term for intellectual disability) in a specific region of India. It examines the differences in prevalence between urban and rural populations, as well as potential risk factors.[7]

Please note that the term "mental retardation" is outdated and considered offensive. The preferred term is "intellectual disability."

Causes

Causes of Mental Retardation

1. Genetic (probably in 5% of cases):

i. Chromosomal abnormalities (such as Down’s syndrome, Fragile-X syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, Klinefelter’s syndrome)

ii. Inborn errors of metabolism, involving amino acids, lipids, carbohydrates, purines, and mucopolysaccharides.

iii. Single-gene disorders (such as tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, dystrophia myotonica)

iv. Cranial anomalies (such as microcephaly)

2. Perinatal causes (probably in 10% of cases):

i. Infections (such as rubella, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, cytomegalo-inclusion body disease)

ii. Prematurity

iii. Birth trauma

iv. Hypoxia

v. Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR)

vi. Kernicterus

vii. Placental abnormalities

viii. Drugs during first trimester.

3. Acquired physical disorders in childhood (probably in 2-5% of cases):

i. Infections, especially encephalopathies

ii. Cretinism

iii. Trauma

iv. Lead poisoning

v. Cerebral palsy.

4. Sociocultural causes (probably in 15% of cases):

i. Deprivation of sociocultural stimulation.

5. Psychiatric disorders (probably in 1-2% of cases):

i. Pervasive developmental disorders (such as Infantile autism)

ii. Childhood onset schizophrenia. [1]

6. Health problems:

Diseases like whooping cough, measles, or meningitis can cause mental disability. It can also be caused by not getting enough medical care, or by being exposed to poisons like lead or mercury.

7. Iodine deficiency:

It affecting approximately 2 billion people worldwide, is the leading preventable cause of mental disability in areas of the developing world where iodine deficiency is endemic.

Iodine deficiency also causes goiter, an enlargement of the thyroid gland. [2]

Risk Factors

Risk factors of Mental Retardation

There are many risk factors for intellectual disability (ID), formerly known as mental retardation. These risk factors can be broadly categorized into:

1. Biomedical factors:

Genetic factors:

These include chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., Down syndrome), single gene disorders (e.g., Fragile X syndrome), and inherited metabolic disorders.

Prenatal factors:

These include maternal infections during pregnancy (e.g., rubella, cytomegalovirus), exposure to toxins (e.g., alcohol, lead), and maternal malnutrition.

Perinatal factors:

These include complications during labor and delivery, such as oxygen deprivation, premature birth, and low birth weight.

Postnatal factors:

These include brain injuries, infections (e.g., meningitis, encephalitis), and exposure to toxins.

2. Social factors:

Poverty:

Poverty can limit access to healthcare, education, and other resources that are important for healthy child development.

Malnutrition:

Malnutrition, especially during the first few years of life, can have a negative impact on brain development.

Lack of stimulation:

Children who do not receive adequate stimulation and interaction with caregivers may not develop their full potential.

Parental mental health problems:

Parents with mental health problems may have difficulty providing the care and support that their children need.

3. Behavioral factors:

Child abuse and neglect:

Child abuse and neglect can lead to physical and emotional trauma, which can affect brain development and increase the risk of ID.[8]

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of Mental Retardation

The pathogenesis of intellectual disability (ID) is complex and multifactorial, involving a wide range of genetic, environmental, and social factors. It is not a single disease but rather a group of conditions with diverse etiologies.

Genetic Factors:

- Chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome)

- Single gene mutations (e.g., phenylketonuria, Rett syndrome)

- Copy number variations (CNVs)

- Epigenetic modifications

Environmental Factors:

- Prenatal exposures (e.g., infections, toxins, maternal malnutrition)

- Perinatal complications (e.g., premature birth, hypoxia)

- Postnatal events (e.g., traumatic brain injury, infections)

Social Factors:

- Poverty and deprivation

- Malnutrition

- Lack of stimulation and early intervention

This book Neurodevelopmental Disabilities: Clinical Principles and Practice provides a comprehensive overview of the pathogenesis of various neurodevelopmental disabilities, including intellectual disability. It covers genetic, environmental, and social factors, as well as the neurobiological mechanisms underlying these conditions.[9]

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology of Mental Retardation

The term "mental retardation" is outdated and considered offensive. The preferred term is "intellectual disability" (ID).

The pathophysiology of intellectual disability (ID) is complex and multifactorial, involving a wide range of genetic, environmental, and social factors. It is not a single disease but rather a group of conditions with diverse etiologies.

Genetic Factors:

- Chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome)

- Single gene mutations (e.g., phenylketonuria, Rett syndrome)

- Copy number variations (CNVs)

- Epigenetic modifications

These genetic alterations can disrupt brain development at various stages, leading to structural and functional abnormalities. They may affect neuronal migration, differentiation, synaptogenesis, and neurotransmitter systems.

Environmental Factors:

- Prenatal exposures (e.g., infections, toxins, maternal malnutrition)

- Perinatal complications (e.g., premature birth, hypoxia)

- Postnatal events (e.g., traumatic brain injury, infections)

These environmental factors can cause damage to the developing brain, leading to neuronal loss, gliosis, and inflammation. They may also disrupt critical periods of brain plasticity.

Social Factors:

- Poverty and deprivation

- Malnutrition

- Lack of stimulation and early intervention

These social factors can exacerbate the effects of genetic and environmental risk factors, leading to further impairments in cognitive and adaptive functioning.

This book Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports provides a comprehensive overview of intellectual disability, including its definition, classification, etiology, and assessment. It also discusses the various systems of supports that can be provided to individuals with ID to help them reach their full potential.[8]

Types

Types

A classification of mental retardation on the basis of IQ ( Intelligence Quotient, which is equal to mental age, i.e. MA, divided by chronological age, i.e. CA, multiplied by 100; i.e. IQ = MA/CA × 100).

1. Mild Mental Retardation:

- This is the commonest type of mental retardation, accounting for 85-90% of all cases.

- The diagnosis is made usually later than in other types of mental retardation.

- In the preschool period (before 5 years of age), these children often develop like other normal children, with very little deficit.

- Later, they often progress up to the 6th class (grade) in school and can achieve vocational and social self sufficiency with a little support.

- Only under stressful conditions or in the presence of an associated disease, supervised care may be needed.

- This group has been referred to as ‘educable’ in a previous educational classification of mental retardation. [1]

Some of the following symptoms of mild MR include:

- taking longer to learn to talk, but communicating well once they know how

- being fully independent in self-care when they get older

- having problems with reading and writing

- social immaturity

- inability to deal with the responsibilities of marriage or parenting

- benefiting from specialized education plans

- having an IQ range of 50 to 69 [3]

2. Moderate Mental Retardation:

- About 10% of all persons with mental retardation have an IQ between 35 and 50.

- In the educational classification, this group was earlier called as ‘trainable’, although many of these persons can also be educated.

- In the early years, despite a poor social awareness, these children can learn to speak.

- Often, they drop out of school after the 2nd class (grade).

- They can be trained to support themselves by performing semiskilled or unskilled work under supervision.

- A mild stress may destabilise them from their adaptation; thus they work best in supervised occupational settings. [1]

If your child has moderate MR, they may exhibit some of the following symptoms:

- are slow in understanding also using language

- may have some difficulties with communication

- can learn basic reading, writing, and counting skills

- are generally unable to live alone

- can often get around on their own to familiar places

- can take part in various types of social activities

- generally have an IQ range of 35 to 49 [3]

3. Severe Mental Retardation:

- Severe mental retardation is often recognised early in life with poor motor development (significantly delayed developmental milestones) also absent or markedly delayed speech and other communication skills.

- Later in life, elementary training in personal health care can be given and they can be taught to talk.

- At best, they can perform simple tasks under close supervision. In the earlier educational classification, they were called as ‘dependent’. [1]

Symptoms include:

- noticeable motor impairment

- severe damage to, or abnormal development of, their central nervous system

- generally have an IQ range of 20 to 34 [3]

4. Profound Mental Retardation:

- This group accounts for about 1-2% of all persons with mental retardation.

- The associated physical disorders, which often contribute to mental retardation, are common in this subtype.

- The achievement of developmental milestones is markedly delayed.

- They often need nursing care or ‘life support’ under a carefully planned and structured environment (such as group homes or residential placements). [1]

Symptoms of profound MR include:

- inability to understand or comply with requests or instructions

- possible immobility

- incontinence

- very basic nonverbal communication

- inability to care for their own needs independently

- the need of constant help and supervision

- having an IQ of less than 20 [3]

Clinical Features

Clinical Features

The clinical features of intellectual disability (ID) vary depending on the severity of the disability and the underlying cause. However, some common features include:

Intellectual functioning:

Significantly below average intellectual functioning, as measured by standardized intelligence tests (IQ score of 70 or below).

Adaptive functioning:

Significant limitations in adaptive behavior, which refers to the skills necessary for everyday life, such as communication, self-care, social/interpersonal skills, and practical skills.

Developmental delays:

Delays in reaching developmental milestones, such as sitting, crawling, walking, talking, and learning.

Learning difficulties:

Difficulties with learning and academic skills, such as reading, writing, and math.

Social and emotional difficulties:

Difficulties with social interactions, communication, and emotional regulation.

It’s important to note that individuals with intellectual disability are a diverse group, and not everyone will experience all of these features. Additionally, the severity of these features can vary widely.

This book Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports provides a comprehensive overview of intellectual disability, including its definition, classification, etiology, and assessment. It also discusses the various systems of supports that can be provided to individuals with ID to help them reach their full potential.[8]

Sign & Symptoms

Sign & Symptoms

There are many signs:

- Children with developmental disabilities may learn to sit up, to crawl, or to walk later than other children, or they may learn to talk later.

- Both adults and children with intellectual disabilities may also have trouble in speaking, find it hard to remember things, have trouble understanding social rules.

- Have trouble discerning cause and effect.

- Trouble solving problems.

- Have trouble thinking logically.

- In early childhood mild disability (IQ 60-70) may not be obvious, and may not be diagnosed until they begin school.

- Even when poor academic performance is recognized, it may take expert assessment to distinguish mild mental disability from learning disability or behaviour problems.

- As they become adults, many people can live independently and may be considered by others in their community as "slow" rather than foolish.

- Moderate disability (IQ 50-60) is nearly always obvious within the first years of life.

- These people will encounter difficulty in school, at home, and in the community.

- In many cases they will need to join special, usually separate, classes in school, but they can still progress to become functioning members of society.

Other symptoms:

- As adults they may live with their parents, in a supportive group home, or even semi-independently with significant supportive services to help them, for example, manage their finances.

- Among people with intellectual disabilities, only about one in eight will score below 50 on IQ tests.

- A person with a more severe disability will need more intensive support and supervision in his or her entire life.

- The limitations of cognitive function will cause a child to learn and develop more slowly than a typical child.

- Children may take longer to learn to speak, walk, and take care of their personal needs such as dressing or eating.

- Learning will take them longer, require more repetition, and there may be some things they cannot learn.

- The extent of the limits of learning is a function of the severity of the disability.

- Nevertheless, virtually every child is able to learn, develop, and grow to some extent. [2]

Clinical Examination

Clinical Examination

The clinical examination of individuals with intellectual disability (ID) involves a comprehensive assessment of various domains:

Developmental History:

Detailed information about the individual’s developmental milestones, including motor, language, cognitive, and social-emotional development. This helps to identify any delays or deviations from typical development.

Medical History:

Information about any medical conditions, genetic disorders, or prenatal/perinatal complications that could contribute to ID.

Family History:

Information about any family members with ID or other developmental disorders, which may suggest a genetic predisposition.

Physical Examination:

A thorough physical examination to identify any physical features or anomalies associated with specific genetic syndromes or medical conditions.

Neurological Examination:

Assessment of the individual’s neurological function, including reflexes, motor skills, sensory function, and cranial nerves.

Cognitive Assessment:

Standardized intelligence tests to assess the individual’s intellectual functioning, as well as measures of adaptive behavior to assess their ability to function in everyday life.

Speech and Language Assessment:

Assessment of the individual’s communication skills, including receptive and expressive language, articulation, and pragmatics.

Behavioral Assessment:

Assessment of the individual’s behavior, including any emotional or behavioral problems that may be present.

Psychiatric Assessment:

Assessment of the individual’s mental health, including any co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

Additional Assessments:

As needed, additional assessments may be conducted, such as genetic testing, neuroimaging, or metabolic testing.

This book Clinical Assessment of Intellectual Disability provides a comprehensive overview of the clinical assessment of individuals with intellectual disability. It covers various assessment tools and techniques, as well as the interpretation of assessment findings. It also discusses the importance of considering the individual’s cultural and linguistic background in the assessment process.[10]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

According to the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV), there are three criteria before a person is considered to have a developmental disability.

An IQ below 70, significant limitations in two or more areas of adaptive behaviour (i.e, ability to function at age level in an ordinary environment), and evidence that the limitations became apparent in childhood.

It is formally diagnosed by professional assessment of intelligence and adaptive behaviour.

The following ranges, based on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), are in standard use today:

- Class IQ.

- Profound mental retardation below 20.

- Severe mental retardation 20-34.

- Moderate mental retardation 35-49.

- Mild mental retardation 50-69.

- Borderline mental retardation 70-79. [2]

The diagnosis is made by the following steps:

History

General physical examination

Detailed neurological examination

Mental status examination, for the assessment of associated psychiatric disorders and the clinical assessment of the level of intelligence.

Investigations:

i. Routine investigations.

ii. Urine test, e.g. for phenylketonuria, maple syrup urine disease.

iii. EEG, especially in presence of seizures. iv. Blood levels, for inborn errors of metabolism.

v. Chromosomal studies, e.g. in Down’s syndrome, prenatal (by amniocentesis or chorionic villus biopsy) and postnatal.

vi. CT scan or MRI scan of brain, e.g. in tuberous scle ro sis, focal seizures, unexplained neurological syndromes, anomalies of skull confi guration, severe or profound mental retardation without any apparent cause, toxoplasmosis.

vii. Thyroid function tests, particularly when cretinism is suspected.

viii. Liver function tests, e.g. in mucopolysaccharidosis.

Psychological tests:

The commonly used tests for measurement of intelligence i.e.:

i. Seguin form board test.

ii. Stanford-Binet, Binet-Simon or Binet-Kamath tests.

iii. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) for 6½ to 16 years of age.

iv. Wechsler’s Preschool also Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) for 4 to 6½ years of age.

v. Bhatia’s battery of performance tests.

vi. Raven’s progressive matrices (e.g. coloured, standard and advanced).

The tests used for the assessment of adaptive behaviour include:

i. Vineland Social Maturity Scale (in other words; VSMS).

ii. Denver Development Screening Test (in other words; DDST).

iii. Gesell’s Development Scale. [1]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis of Mental Retardation

The differential diagnosis of intellectual disability (ID) involves considering various conditions that can present with similar symptoms. This is important to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate intervention.

Some of the key differential diagnoses of ID include:

Specific learning disorders:

These disorders affect specific academic skills (e.g., reading, writing, math) but do not involve global intellectual impairment.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD):

ASD is characterized by deficits in social communication and interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors. While intellectual disability can co-occur with ASD, it is not a defining feature.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD):

ADHD involves difficulties with attention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. It can affect academic and social functioning, but it does not necessarily involve intellectual impairment.

Communication disorders:

These disorders affect speech, language, or communication skills. They can co-occur with ID, but they are not the same thing.

Neurocognitive disorders:

These disorders involve acquired cognitive decline due to medical conditions or brain injury. They are typically seen in older adults and can mimic the symptoms of ID.

Sensory impairments:

Hearing or vision loss can affect cognitive and adaptive functioning, potentially leading to a misdiagnosis of ID.

Mental health disorders:

Conditions such as anxiety, depression, or trauma can impact cognitive and adaptive functioning, especially in children.

This book Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports provides a comprehensive overview of intellectual disability, including its definition, classification, etiology, and assessment. It also discusses the differential diagnosis of ID and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to assessment.[8]

Complications

Complications

Individuals with intellectual disability (ID) may experience various complications throughout their lives, depending on the severity of their disability and the underlying cause. These complications can affect their physical, mental, and social well-being.

Some common complications of ID include:

Mental Health Problems:

Individuals with ID are at a higher risk of developing mental health disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder. This may be due to the challenges they face in adapting to the demands of everyday life, as well as the stigma and discrimination they may experience.

Behavioral Problems:

Some individuals with ID may exhibit challenging behaviors, such as aggression, self-injury, or repetitive behaviors. These behaviors can be difficult for caregivers to manage and may require specialized interventions.

Epilepsy:

Seizures are more common in individuals with ID, especially those with severe or profound disability. Epilepsy can further impair cognitive and adaptive functioning and may require ongoing treatment.

Physical Health Problems:

Individuals with ID may have a higher risk of certain physical health problems, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. This may be due to genetic factors, lifestyle factors, or the side effects of medications.

Social Isolation:

Individuals with ID may experience social isolation and difficulty forming and maintaining relationships due to their communication and social skills deficits. This can lead to loneliness and further exacerbate mental health problems.

This book Intellectual Disability: A Clinical Guide for Medical and Mental Health Professionals provides a comprehensive overview of intellectual disability, including its definition, classification, etiology, and assessment. It also discusses the various complications associated with ID and the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to treatment.[11]

Investigations

Investigation

The investigation of intellectual disability (ID) involves a comprehensive assessment of various domains to determine the cause and severity of the disability, as well as to identify any co-occurring conditions. This assessment typically includes:

Developmental History:

Detailed information about the individual’s developmental milestones, including motor, language, cognitive, and social-emotional development. This helps to identify any delays or deviations from typical development.

Medical History:

Information about any medical conditions, genetic disorders, or prenatal/perinatal complications that could contribute to ID.

Family History:

Information about any family members with ID or other developmental disorders, which may suggest a genetic predisposition.

Physical Examination:

A thorough physical examination to identify any physical features or anomalies associated with specific genetic syndromes or medical conditions.

Neurological Examination:

Assessment of the individual’s neurological function, including reflexes, motor skills, sensory function, and cranial nerves.

Cognitive Assessment:

Standardized intelligence tests to assess the individual’s intellectual functioning, as well as measures of adaptive behavior to assess their ability to function in everyday life.

Speech and Language Assessment:

Assessment of the individual’s communication skills, including receptive and expressive language, articulation, and pragmatics.

Behavioral Assessment:

Assessment of the individual’s behavior, including any emotional or behavioral problems that may be present.

Psychiatric Assessment:

Assessment of the individual’s mental health, including any co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

Additional Investigations:

Depending on the initial findings, further investigations may be warranted, such as:

- Genetic testing: To identify any chromosomal abnormalities or genetic mutations associated with ID.

- Neuroimaging: To assess the structure and function of the brain, such as MRI or CT scans.

- Metabolic testing: To rule out metabolic disorders that can cause ID.

- Blood tests: To check for infections, hormonal imbalances, or nutritional deficiencies.

- Hearing and vision tests: To rule out sensory impairments that can affect cognitive and adaptive functioning.

This book Clinical Assessment of Intellectual Disability provides a comprehensive overview of the clinical assessment of individuals with intellectual disability. It covers various assessment tools and techniques, as well as the interpretation of assessment findings. It also discusses the importance of considering the individual’s cultural and linguistic background in the assessment process.[10]

Treatment

Treatment of Mental Retardation

There is no cure for intellectual disability (ID), but various treatments and interventions can help individuals with ID reach their full potential and improve their quality of life. The treatment approach is often multi-faceted and tailored to the individual’s specific needs and abilities.

Early Intervention:

Early intervention programs are crucial for young children with ID. These programs provide specialized services such as speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, and special education to address developmental delays and enhance cognitive, social, and motor skills.

Behavioral Interventions:

Behavioral interventions are used to address challenging behaviors that may be associated with ID. These interventions focus on teaching new skills, reinforcing positive behaviors, and reducing problem behaviors through various techniques like positive reinforcement, shaping, and prompting.

Medications:

Medications may be prescribed to manage specific symptoms or co-occurring conditions associated with ID, such as seizures, anxiety, depression, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Educational Support:

Individuals with ID may require specialized educational support to address their learning needs and achieve academic success. This may involve individualized education plans (IEPs), special education classes, or assistive technology.

Vocational Training:

Vocational training programs can help individuals with ID acquire the skills necessary for employment and independent living. These programs may focus on specific job skills, social skills, and self-advocacy.

Family Support:

Family support is essential for individuals with ID and their families. This may involve counseling, education, respite care, and support groups to help families cope with the challenges of raising a child with ID.

This book Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports provides a comprehensive overview of intellectual disability, including its definition, classification, etiology, and assessment. It also discusses various interventions and supports that can be provided to individuals with ID to help them reach their full potential.[8]

Prevention

Prevention

Primary Prevention:

This consists of i.e.:

- In general, Improvement in socioeconomic condition of society at large, aiming at elimination of under-stimulation, malnutrition, prematurity also perinatal factors.

- Moreover, Education of lay public, aiming at removal of the misconceptions about individuals with mental retardation.

- Medical measures for good perinatal medical care to prevent infections, trauma, excessive use of medications, malnutrition, obstetric complications, and diseases of pregnancy.

- Besides this, Universal immunisation of children with BCG, polio, DPT, and MMR.

- Facilitating research activities to study the causes of mental retardation also their treatment.

- All in all, Genetic counselling in at risk parents, e.g. in phenylketonuria, Down’s syndrome.

Secondary Prevention:

- Basically, Early detection and treatment of preventable disorders, e.g. phenylketonuria (low phenylalanine diet), maple syrup urine disease (low branched amino-acid diet) and hypothyroidism (thyroxine).

- Detection of handicaps in sensory, either motor or behavioural areas with early remedial measures and treatment.

- Early treatment of correctable disorders, e.g. infections (antibiotics), skull configuration anomalies (surgical correction).

- Besides this, Early recognition of presence of mental retardation. A delay in diagnosis may cause unfortunate delay in rehabilitation.

- As far as possible, individuals with mental retardation should be integrated with normal individuals in society, also any kind of segregation or discrimination should be actively avoided.

- Lastly, They should be provided with facilities to enable them to reach their own full potential. However, there is a role of special schools for those with more severe mental retardation.

Tertiary Prevention:

Adequate treatment of psychological also behavioural problems.

Behaviour modification, using the principles of positive also negative reinforcement.

Rehabilitation in vocational, physical, also social areas, commensurate with the level of disability.

Parental counselling is extremely important to lessen the levels of stress, teaching them to adapt to the situation, enlisting them (especially parents) as co-therapists, and encouraging formation of parents’ or carers’ organisation and self-help groups.

Either Institutionalisation or residential care may be needed for individuals with profound mental retardation.

Legislation: In 1995, the ‘Persons with Disability Act’ came into being in India. This act envisages mandatory support for prevention, early detection, education, employment, and other facilities for the welfare of persons with disabilities in general, and mental retardation in particular.

This Act provides for affirmative action also non-discrimination of persons with disabilities.

In 1999, the ‘National Trust Act’ came in to force. All in all, This Act proposes to involve the parents of mentally challenged persons and voluntary organisations in setting up and running a variety of services and facilities with governmental funding.

Homeopathic Treatment

Homoeopathic Treatment

Abrotanum:

Marked emaciation of legs, old looking skin, flabby and hangs loose in folds, cannot hold up the head.

In detail, Sensitive tendency, cross, irritable, depressed peevish, cruel troubling others kills small insects, beats pets. No manners. Additionally, It’s difficult for him to enjoy with others.

Baryta Carbonica:

Dwarfish appearance. Additionally, Mentally deficient and physically weak and short.

Typical picture of cretinism having short stature swollen abdomen, puffy face, enlarged glands, thick lips also idiotic appearance.

Idiotic foolish, with loss of memory, shy, nervous in front of strangers, hides behind the furniture, bashful, timid, easily frightened children do not want to play.

Sits in the corner and throws stones at strangers. Besides this, Inattentive, milestones are delayed, late learning to walk. This could be either due to defects of development or due to premature degeneration.

Calcarea Carbonica:

Children who grow fat chalky look with red face, large belly like inverted saucer with large head also open fontanelles and sutures.

Pale skin, soft bones, who sweat easily especially on the backside and neck, slowness, delayed skills-walking, talking, etc., slow comprehension in school, poor recall, mistakes in reading also writing.

Forgetfulness, forgets what he has read soon after. Fear of dark, spiders’ insects’ animals and ghosts, startles easily. Cannot calculate. Additionally, Cannot do deep thinking. Wants to be magnetized.

Fungi group (Remedies):

It has been seen that the group of fungus remedies is useful in cases of mental retardation. Following are the common symptoms found i.e.:

- Absent minded.

- Confused behaviour.

- Dullness, difficulty in thinking.

- Indifference, apathy to everything.

- Memory weakness.

- Awkwardness.

- Concentration difficult.

- Forgetful.

- Indolence, aversion to work.

- Imbecility.

Medorrhinum:

- Dullness and sluggishness in children.

- Forgets his own name.

- Hurry, imbecility, impatient, irritability, difficult concentration.

- Weakness of memory.

- Makes mistakes in spelling.

- Excitement while writing.

- Confused mind.

- Delusions, hallucinations, illusions of animals.

- It has organic brain syndrome which includes delirium, dementia, head excitement, etc.

- Religious affections, selfishness.

- Slow learners. [2]

Diet & Regimen

Diet & Regimen

Individuals with intellectual disability (ID) may have specific dietary and regimen needs depending on the severity of their disability, associated medical conditions, and individual preferences. However, some general recommendations can be made.

Diet:

- Balanced and nutritious diet: A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and healthy fats is essential for overall health and well-being.

- Adequate hydration: Ensure adequate fluid intake to prevent dehydration, which can affect cognitive function.

- Modified textures: Depending on the individual’s oral-motor skills and swallowing abilities, food may need to be modified in texture, such as pureeing or chopping.

- Dietary restrictions: Some individuals with ID may have specific dietary restrictions due to associated medical conditions, such as allergies or metabolic disorders. It is crucial to consult with a healthcare professional or registered dietitian to tailor the diet to their specific needs.

- Vitamin and mineral supplements: In some cases, vitamin and mineral supplements may be recommended to address specific deficiencies or support overall health.

Regimen:

- Regular physical activity: Regular physical activity is crucial for maintaining a healthy weight, promoting cardiovascular health, and improving mood and cognitive function. The type and intensity of exercise should be adjusted to the individual’s abilities and preferences.

- Structured routine: A structured daily routine can provide predictability and stability for individuals with ID, reducing anxiety and promoting a sense of control.

- Adequate sleep: Sufficient sleep is essential for cognitive function, mood regulation, and overall health.

- Social interaction: Encourage social interaction and participation in activities that the individual enjoys. Social engagement can enhance well-being and reduce the risk of social isolation.

- Stress management: Help individuals with ID develop healthy coping mechanisms for stress, such as relaxation techniques or mindfulness exercises.

This book Nutrition for Individuals with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities provides a comprehensive guide to nutrition for individuals with ID, covering topics such as dietary needs, meal planning, feeding challenges, and strategies for promoting healthy eating habits.[12]

Do’s and Don'ts

Do’s & Don’ts

intellectual disabilities Do’s & Dont’s

Do’s when interacting with individuals with intellectual disabilities:

- Treat them with respect and dignity: Everyone deserves to be treated with respect, regardless of their abilities.

- Speak directly to the person: Even if they have a support person with them, address the individual directly.

- Be patient and understanding: Communication may take longer or require different approaches. Be willing to adjust your communication style.

- Offer support and encouragement: Help them participate in activities and reach their goals.

- Focus on their strengths and abilities: Everyone has unique talents and skills.

- Educate yourself: Learn about intellectual disability and the challenges individuals may face.

- Advocate for inclusion: Support their participation in all aspects of community life.

- Be kind and compassionate: Show empathy and understanding.

- Celebrate their achievements: Recognize their efforts and accomplishments, no matter how small they may seem.

Don’ts when interacting with individuals with intellectual disabilities:

- Make assumptions about their abilities: Don’t underestimate their potential.

- Talk down to them or patronize them: Speak to them as you would any other adult.

- Ignore their needs or feelings: They deserve to have their needs met and their feelings acknowledged.

- Exclude them from activities: Everyone should have the opportunity to participate.

- Discriminate against them: They have the same rights as everyone else.

- Be impatient or dismissive: Give them time to process information and respond.

- Make fun of them or bully them: This is hurtful and harmful.

- Ignore their support person: If they have a support person, include them in the conversation.

- Spread misinformation or stereotypes: Learn the facts about intellectual disability.

Remember, people with intellectual disabilities are individuals first and foremost. Treat them with the same respect and consideration you would give to anyone else.

Terminology

Terminology

Preferred Terminology:

- Intellectual disability: This is the current and accepted term used to describe individuals with significant limitations in intellectual functioning (e.g., reasoning, learning, problem-solving) and adaptive behavior (e.g., communication, social skills, daily living).

- Person with intellectual disability: This phrase emphasizes the person first, rather than their disability.

- Developmental disability: This broader term encompasses a range of conditions that affect development, including intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, and cerebral palsy.

Other Terms:

- Cognitive impairment: This term refers to a general decline in cognitive function, including memory, thinking, and reasoning. It can be caused by various factors, such as aging, brain injury, or dementia.

- Adaptive behavior: This refers to the collection of conceptual, social, and practical skills that people learn and use in their everyday lives.

It is important to use respectful and inclusive language when discussing intellectual disability. By using the preferred terminology, we can help to reduce stigma and promote understanding and acceptance of individuals with intellectual disabilities.

Homoeopathic Term

Homeopathic articles on mental retardation may use specific terms and concepts based on their understanding of health and disease. Here are some common terminologies you may encounter in such articles, along with their meanings:

Miasm:

A miasm is a predisposition to certain types of diseases, often passed down through generations. Homeopaths believe that addressing the underlying miasm is crucial for treating chronic conditions like mental retardation.

Vital force:

The vital force is the energy that animates the body and maintains health. Homeopaths believe that disease arises due to a disturbance in the vital force, and treatment aims to restore its balance.

Remedy:

A homeopathic remedy is a highly diluted substance that, according to the principle of "like cures like," can stimulate the body’s healing response to a similar ailment.

Repertorization:

This is the process of selecting the most appropriate homeopathic remedy based on the patient’s symptoms and individual characteristics.

Potency:

The potency of a homeopathic remedy refers to the number of times it has been diluted and succussed (shaken vigorously). Higher potencies are believed to have a deeper and longer-lasting effect.

Aggravation:

This is a temporary worsening of symptoms after taking a homeopathic remedy, which is considered a sign that the remedy is working.

Constitutional remedy:

This is a remedy that matches the patient’s overall constitution or inherent tendencies, and it is believed to be effective for treating a wide range of chronic conditions.

Nosode:

A nosode is a homeopathic remedy prepared from diseased tissue or bodily fluids. It is used to treat conditions that share similar characteristics with the source material.

Examples of homeopathic remedies mentioned in articles on mental retardation:

Baryta Carbonica:

This remedy is often used for children with delayed development, slow learning, and poor memory.

Calcarea Carbonica:

This remedy is indicated for children who are heigher weight, have delayed milestones, and show slow mental development.

Medor $rhinum:

This remedy is used for children with behavioral problems, hyperactivity, and difficulty concentrating.

Silicea:

This remedy is often prescribed for children with weak constitutions, poor coordination, and a tendency to be shy and introverted.

References

References

- A Short Textbook of Psychiatry by Niraj Ahuja / Ch 13.

- Homeopathy in treatment of Psychological Disorders by Shilpa Harwani / Ch 20.

- https://www.healthline.com/symptom/mental-retardation.

- Prevalence of intellectual disability in India: A meta-analysis (2022).

- National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16.

- (PDF) Intellectual Disability in India: An overview.

- (PDF) Prevalence of mental retardation in urban and rural populations of the goiter zone in Northwest India.

- Intellectual Disability: Definition, Classification, and Systems of Supports (12th Edition) by American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) (2021).

- Neurodevelopmental Disabilities: Clinical Principles and Practice by Michael Shevell (Editor), (2nd edition, 2021). Published by Mac Keith Press.

- Clinical Assessment of Intellectual Disability (2nd Edition) by John L. Matson (Editor) (2016). Published by Springer Publishing Company.

- Intellectual Disability: A Clinical Guide for Medical and Mental Health Professionals by Matthew P. Janicki, James C. Harris (2017). Published by Springer Publishing Company.

- Nutrition for Individuals with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities by M. Tracy Hildreth, et al. (2016). Published by the Rural Institute for Inclusive Communities, University of Montana.

Also Search As

Also Search As

To search for homeopathic articles on intellectual disability (the preferred term for mental retardation), you can use the following resources and methods:

Online Databases:

- Homeopathic Journals: Many homeopathic journals publish articles on various health conditions, including intellectual disability. You can search their archives or use their search functions to find relevant articles. Some popular homeopathic journals include:

- The American Journal of Homeopathic Medicine

- The European Journal of Integrative Medicine

- The Indian Journal of Research in Homeopathy

- Online Libraries: Several online libraries and databases offer access to homeopathic literature. You can search these resources using keywords like "homeopathy," "intellectual disability," "developmental delay," or specific homeopathic remedies.

- Homeopathic Journals: Many homeopathic journals publish articles on various health conditions, including intellectual disability. You can search their archives or use their search functions to find relevant articles. Some popular homeopathic journals include:

Search Engines:

- Google Scholar: This search engine specializes in academic literature and can help you find research articles and case studies related to homeopathy and intellectual disability.

- General Search Engines: You can use search engines like Google or Bing to search for articles on homeopathic websites, blogs, and forums. However, it is important to critically evaluate the information found online and consult with a qualified homeopathic practitioner before making any treatment decisions.

Homeopathic Organizations:

- National Center for Homeopathy (NCH): The NCH is a non-profit organization that promotes homeopathy and offers resources for practitioners and patients. Their website may have articles or publications on intellectual disability.

- Other Homeopathic Organizations: Many other national and international homeopathic organizations exist. You can search their websites or contact them for information on relevant articles and resources.

Additional Tips:

- Use specific keywords: Include terms like "homeopathy," "intellectual disability," "developmental delay," "case studies," "clinical trials," and the names of specific homeopathic remedies.

- Look for peer-reviewed articles: Peer-reviewed articles are more likely to be reliable and scientifically sound.

- Consult with a homeopathic practitioner: A qualified homeopathic practitioner can guide you in finding relevant articles and interpreting the information.

Disclaimer: Please note that homeopathic approaches to intellectual disability are not supported by mainstream scientific evidence, and there is no reliable research to demonstrate their effectiveness. It is always advisable to consult with a qualified healthcare professional for any health concerns.

To search for information on intellectual disability (the preferred term for mental retardation), you can use various approaches:

Online Search Engines:

- Use search terms like "intellectual disability," "cognitive impairment," "developmental delay," or specific conditions associated with intellectual disability (e.g., Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome).

- Be specific in your search query to narrow down results. For example, search for "causes of intellectual disability" or "treatment for intellectual disability."

- Use reputable sources like government websites (.gov), educational institutions (.edu), and non-profit organizations (.org) for reliable information.

Academic Databases:

- If you are looking for research articles or scholarly publications, use academic databases like PubMed, Google Scholar, or ScienceDirect.

- Search for keywords related to your topic of interest, such as "intellectual disability," "epidemiology," "intervention," or "diagnosis."

Libraries:

- Visit your local library or university library to access books, journals, and other resources on intellectual disability.

- Librarians can help you find relevant materials and navigate the library’s catalog.

Professional Organizations:

- Organizations like the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) and the National Association for Down Syndrome (NDSS) offer a wealth of information on intellectual disability, including research, resources, and support services.

- Visit their websites or contact them directly for more information.

Support Groups and Forums:

- Online support groups and forums can be a valuable resource for individuals with intellectual disability, their families, and caregivers.

- These platforms offer a safe space to share experiences, ask questions, and connect with others facing similar challenges.

Remember:

- Always use person-first language when referring to individuals with intellectual disability.

- Be critical of the information you find online. Not all sources are reliable or accurate.

- If you have questions or concerns about intellectual disability, consult with a healthcare professional or specialist.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Mental Retardation?

Definition

Mental retardation is a term for a pattern of persistently slow learning of basic motor and language skills (milestones) during childhood, and a significantly below-normal global intellectual capacity as an adult.

What causes Mental Retardation?

Causes

- Chromosomal abnormalities

- Inborn errors of metabolism

- Single-gene disorders

- Cranial anomalies

- Perinatal causes (Infections, Prematurity, Birth trauma)

- Acquired physical disorders in childhood

- Sociocultural cause

- Psychiatric disorders

- Iodine deficiency

Give the types of Mental Retardation?

What are the symptoms of Mental Retardation?

Symptoms

- Children with developmental disabilities

- Intellectual disabilities

- Have trouble discerning cause and effect.

- Trouble solving problems.

- Have trouble thinking logically

- Poor academic performance

Can homeopathy help with mental retardation?

Homeopathy is a holistic system of medicine that aims to stimulate the body’s natural healing abilities. While there is limited scientific evidence to support its effectiveness for mental retardation, some people believe that homeopathic remedies can help improve cognitive function, reduce behavioral problems, and enhance overall quality of life.

How are homeopathic remedies selected for mental retardation?

Homeopathic treatment is individualized, meaning that the remedy selection is based on the person’s unique symptoms, personality, and medical history. A qualified homeopath will conduct a detailed consultation to determine the most appropriate remedy for each individual.

Is homeopathy safe for children with mental retardation?

Homeopathic remedies are generally considered safe when used under the supervision of a qualified homeopath. However, it is important to inform the homeopath about any other medications or treatments the child is receiving.

Can homeopathy cure mental retardation?

Homeopathy does not claim to cure mental retardation. However, it may help improve the individual’s cognitive abilities, reduce behavioral problems, and enhance their overall well-being.

Should I consult a homeopath for mental retardation?

If you are considering homeopathy for mental retardation, it is important to consult a qualified homeopath who has experience treating this condition. They can assess your child’s individual needs and recommend the most appropriate treatment plan.

Homeopathic Medicines used by Homeopathic Doctors in treatment of Mental Retardation?

Homoeopathic Medicines for Mental Retardation

- Abrotanum

- Baryta Carb

- Calcarea Carb

- Medorrhinum