Parkinson’s Disease

Definition

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second commonest neurodegenerative disease.[1]

Parkinson’s disease has a few synonyms, depending on the nuance you want to convey:

- Paralysis agitans: This is a historical term, literally meaning "shaking paralysis." It’s not commonly used anymore but you might encounter it in older texts.

- Parkinsonism: This is a broader term encompassing Parkinson’s disease and other conditions with similar symptoms.

- Shaking palsy: This is a more informal term that highlights the tremor, a common symptom of Parkinson’s disease.

In most cases, "Parkinson’s disease" is the preferred term for accuracy.

Overview

Epidemiology

Causes

Types

Risk Factors

Pathogenesis

Pathophysiology

Clinical Features

Sign & Symptoms

Clinical Examination

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Complications

Investigations

Treatment

Prevention

Homeopathic Treatment

Diet & Regimen

Do’s and Don'ts

Terminology

References

Also Search As

Overview

Overview of Parkinson’s disease

Generally, PD affects people of all genders of all races, all occupations, and all countries. Additionally, The mean age of onset is about 60 years. The frequency of PD increases with aging, but cases can be seen in patients in their 20s and even younger.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease:

The Indian epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease (PD) displays a complex pattern with fluctuating prevalence rates reported across various studies and geographic regions. Though certain research indicates a decreased prevalence when juxtaposed with Western nations, other investigations underscore a substantial disease burden.

A study conducted in rural Gujarat unveiled an overall crude prevalence of 42.3 per 100,000, accompanied by a heightened prevalence within the over-60 age group (308.9 per 100,000). This study further illuminated the escalating prevalence of PD in correlation with age and a greater prevalence in men compared to women (Surathi et al., 2016).

Another investigation undertaken in Kolkata documented an estimated prevalence of 33 per 100,000 (crude prevalence) and 76 per 100,000 (age-adjusted), thereby accentuating the influence of age on PD prevalence (Das et al., 2010).

Moreover, current research proposes that India may exhibit a higher proportion of early-onset Parkinson’s disease (EOPD) in contrast to Western demographics. EOPD is characterized by the manifestation of motor symptoms before the age of 50. Studies indicate that nearly 40-45% of PD patients in India fall into the EOPD category (Movement Disorders Society, 2023).

These collective findings underscore the considerable burden of PD in India, particularly among the older people population and individuals with EOPD. Further research endeavors are imperative to comprehend the regional fluctuations in prevalence, identify potential risk factors, and formulate effective prevention and treatment strategies tailored to the Indian context.

Causes

Causes of Parkinson’s disease

Most PD cases occur sporadically (~85–90%) and are of unknown cause. Twin studies suggest that environmental factors likely play an important role in patients older than 50 years, with genetic factors being more important in younger patients. Epidemiologic studies also suggest increased risk with exposure to pesticides, rural living, and drinking well water and reduced risk with cigarette smoking and caffeine. However, no environmental factor has yet been proven to cause typical PD.

Viral infections – Post-encephalitic Parkinsonism[1]

Types

Types of Parkinson’s disease

While there is only one primary type of Parkinson’s disease, known as idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, the term "Parkinsonism" encompasses a broader range of conditions that present with similar symptoms. These can be categorized as follows:

Primary Parkinsonism:

- Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease: The most common type, with no known specific cause.

- Atypical Parkinsonian Disorders: Less common neurodegenerative conditions that share some features with Parkinson’s disease but often progress more rapidly and respond less well to treatment. Examples include Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP), Multiple System Atrophy (MSA), and Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD).

Secondary Parkinsonism:

- Drug-Induced Parkinsonism: Caused by certain medications, usually those that block dopamine receptors. Symptoms often resolve once the medication is stopped.

- Vascular Parkinsonism: Resulting from reduced blood flow to the brain, often due to multiple small strokes. Symptoms may fluctuate or progress in a stepwise manner.

- Other Causes: Less common causes include toxins, head trauma, metabolic disorders, and infections. [4]

Risk Factors

Risk factors of Parkinson’s disease:

While the exact cause of Parkinson’s disease remains unknown, a combination of genetic and environmental factors is thought to contribute to its development. The following factors have been identified as potential contributors to an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease:

Age:

- The greatest risk factor for developing Parkinson’s disease is advancing age. The average age of onset is around 60, and the risk continues to increase with age.

Sex:

- Men are more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease than women.

Genetics:

- While most cases of Parkinson’s are sporadic (not directly inherited), having a close relative with Parkinson’s disease can increase your risk. Several specific gene mutations have been associated with familial Parkinson’s disease.

Environmental Exposures:

- Exposure to certain pesticides, herbicides, and heavy metals has been linked to a slightly increased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Head Trauma:

- A history of significant head injuries may also slightly increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Other Factors:

- Additional factors that may influence risk include low caffeine consumption, rural living, and certain dietary factors.

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease:

The pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease is complex and multifactorial, involving a combination of genetic and environmental factors. It’s characterized by the, progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, a region of the brain crucial for movement control. This loss leads to a decrease in dopamine levels in the striatum, disrupting the delicate balance of neurotransmitters and impairing the brain’s ability to initiate and control movement.

Key elements in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease include:

Lewy Bodies:

- These abnormal protein aggregates, composed primarily of alpha-synuclein, are a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease. They are found within the surviving neurons and are thought to contribute to their dysfunction and death.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction:

- Impaired mitochondrial function can lead to energy deficits within neurons, making them more vulnerable to damage and death.

Oxidative Stress:

- Increased production of reactive oxygen species and impaired antioxidant defenses can damage cellular components, including proteins, lipids, and DNA, further contributing to neuronal death.

Neuroinflammation:

- Activation of microglia and astrocytes, the brain’s immune cells, can lead to the release of inflammatory molecules, which can damage neurons and contribute to their loss.

Genetic Factors:

- Several genes have been linked to Parkinson’s disease, both familial and sporadic forms. These genes may contribute to various aspects of the disease pathogenesis, including protein aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress. [6]

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease:

Parkinson’s disease is primarily characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, a region of the brain crucial for movement control. This neuronal loss leads to a significant reduction in dopamine levels in the striatum, disrupting the delicate balance of neurotransmitters and impairing the brain’s ability to initiate and control movement.

Key Elements in the Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease:

Dopamine Depletion:

- The hallmark of Parkinson’s disease is the progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, leading to a significant reduction in dopamine levels in the striatum.

- This dopamine depletion disrupts the basal ganglia circuits, which are responsible for coordinating movement, resulting in the characteristic motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, such as bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, and postural instability.

Lewy Bodies:

- Lewy bodies are abnormal protein aggregates, primarily composed of alpha-synuclein, found within the surviving neurons in Parkinson’s disease.

- These aggregates are believed to contribute to neuronal dysfunction and death, although the exact mechanisms remain unclear.

- The presence of Lewy bodies is a pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease and is also observed in other neurodegenerative disorders, collectively referred to as synucleinopathies.

Neuroinflammation and Oxidative Stress:

- Chronic neuroinflammation and oxidative stress are thought to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease.

- Activated microglia and astrocytes release inflammatory molecules and reactive oxygen species, which can damage neurons and contribute to their loss.

- Mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired protein clearance mechanisms can further exacerbate oxidative stress and contribute to neuronal death.

Non-motor Symptoms:

- Parkinson’s disease is not solely a motor disorder; it also manifests with a variety of non-motor symptoms, including cognitive impairment, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and autonomic dysfunction.

- These non-motor symptoms often precede the onset of motor symptoms and can significantly impact the quality of life of individuals with Parkinson’s disease.

- The pathophysiology of non-motor symptoms is complex and involves dysfunction in various brain regions beyond the basal ganglia, including the brainstem, limbic system, and cortex.

Clinical Features

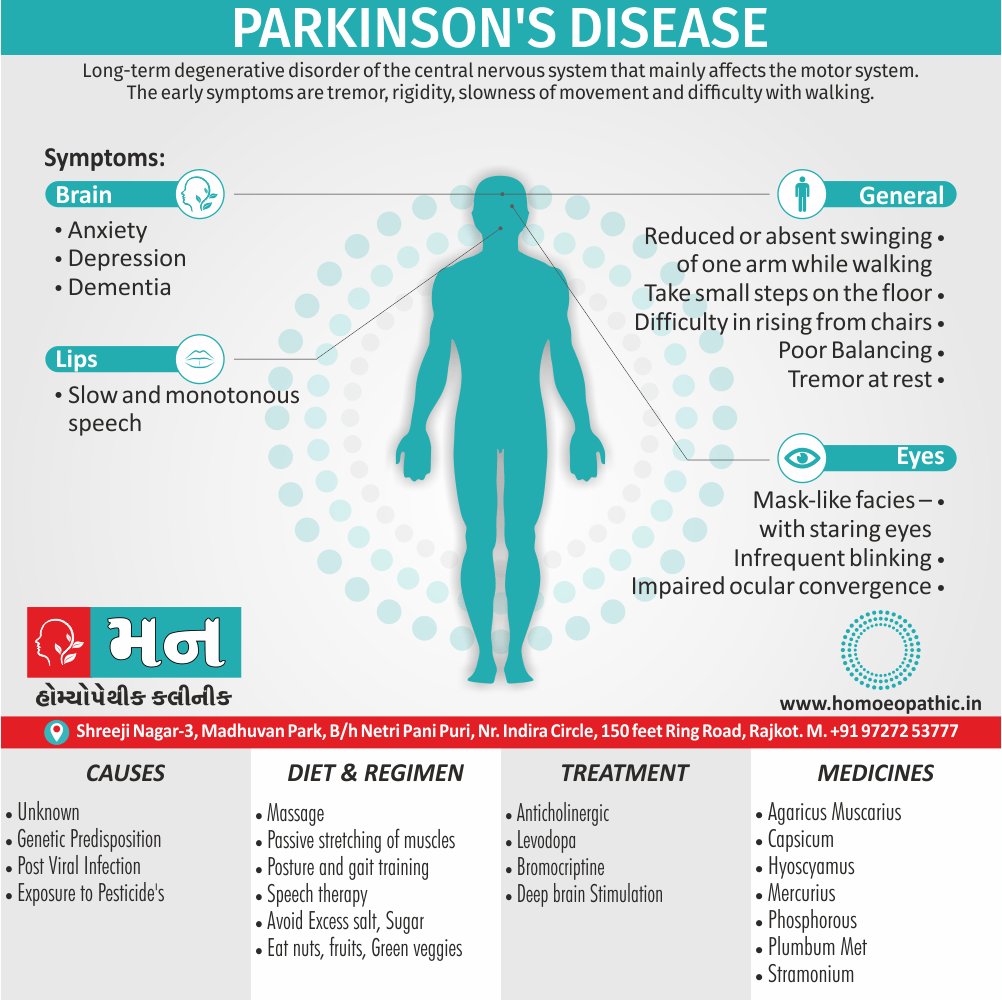

Clinical Features:

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder primarily characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms. The hallmark motor symptoms, often referred to as the Parkinsonian tetrad, include:

Bradykinesia:

- Slowness of movement and difficulty initiating movements. This can affect various aspects of daily life, such as walking, dressing, and eating.

Resting Tremor:

- Involuntary shaking, typically occurring in the hands, arms, or legs at rest. The tremor often diminishes with voluntary movement.

Rigidity:

- Stiffness and resistance to passive movement of the limbs and trunk.

Postural Instability:

- Impaired balance and coordination, leading to an increased risk of falls.

Additional motor symptoms may include:

- Gait disturbances: Shuffling gait with reduced arm swing.

- Micrographia: Small, cramped handwriting.

- Hypomimia: Reduced facial expressions, often described as a "masked face."

- Hypophonia: Soft and monotonous speech.

- Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing.

Non-motor symptoms, which often precede the onset of motor symptoms, include:

- Cognitive Impairment: Problems with attention, memory, and executive functions.

- Depression and Anxiety: Mood disturbances, often associated with the challenges of living with a chronic illness.

- Sleep disturbances: Insomnia, restless leg syndrome, and REM sleep behavior disorder.

- Autonomic dysfunction: Constipation, orthostatic hypotension, urinary problems, and sexual dysfunction.

- Sensory symptoms: Loss of smell (anosmia), pain, and paresthesias (tingling or numbness).

Sign & Symptoms

Sign & Symptoms:

Tremor –

may be first symptom; usually starts in one upper limb; characteristically tremor at rest and described as ‘pill rolling’. Head may be involved. Additionally, Tremors disappear during sleep.

Rigidity –

Plastic or lead pipe, i.e. present to equal extent in opposing muscle groups and if a limb is passively moved the rigidity gives way with a series of slight jerks, or ‘cog wheel’ type, if combined with tremor.

Bradykinesia

– is the cardinal feature of IPD.

– Mask-like facies – with staring eyes.

– Infrequent blinking.

– Impaired ocular convergence.

– Slow also monotonous speech.

– Micrographia.

– Reduced swinging of arms while walking.

– Festinant gait

Other features

Postural disturbance i.e.

– Difficulty in rising from chairs

or rolling over in bed, stooped posture. Disturbance of balance may be seen in the ‘pull’ test, performed by standing behind the patient and pulling back on the shoulders. Instead of moving the arms forward and swaying the trunk, parkinsonian patient may take steps backwards (retropulsion) or even fall back into the examiner’s arms, without any attempt to maintain balance.

Gait disturbance i.e.

– Reduced or absent swinging of one arm while walking is an early sign of Parkinson’s disease. In more advanced cases neither arm may swing; at this stage, the stride length shortens, the trunk appears stiff and the whole body moves in one mass when the patient turns (turning en block). In further advanced disease, patients may appear to ‘freeze’, their feet seem stuck to the floor, or they may take small steps on the floor, often rising on the toes and leaning forwards. A diagnostically important point is that gait in Parkinson’s disease has a narrow base, regardless of how advanced the disease.

Pain i.e.

–Deep cramping sensations may be a primary symptom or secondary to levodopa.

Mental disturbances – (a) Anxiety. (b) Depression. (c) Dementia may be caused by a syndrome similar to Alzheimer’s disease, frontal lobe dementia with a prominent lack of motivation, or a pattern with hallucinations in absence of medication. Postural hypotension – can be caused by antiparkinsonian drugs. It should be considered in any patient who is falling or complains of lack of energy while walking.[1]

Dyskinesia i.e.

– in the form of writing, swinging movements of limbs and trunks are typically caused by excessive levodopa, but may occur with dopamine agonists.

Clinical Examination

Clinical Examination:

The clinical examination of Parkinson’s disease primarily focuses on identifying and assessing the characteristic motor and non-motor symptoms associated with the condition. A comprehensive evaluation typically includes the following components:

Medical History:

- Detailed history of the patient’s symptoms, including their onset, progression, and impact on daily life.

- Family history of Parkinson’s disease or other neurological disorders.

- Past medical history, including medication use, surgeries, and exposures to potential environmental toxins.

Neurological Examination:

Motor Assessment:

- Observation of posture, gait, and balance.

- Assessment of bradykinesia through tasks like finger tapping, hand opening and closing, and pronation-supination of the hands.

- Evaluation of rigidity through passive movement of the limbs.

- Assessment of resting tremor, its amplitude, and frequency.

- Testing for postural instability using the pull test.

- Evaluation of facial expressions, speech, and swallowing.

Non-motor Assessment:

- Cognitive evaluation, including tests of attention, memory, and executive functions.

- Screening for depression and anxiety.

- Inquiry about sleep disturbances, autonomic symptoms, and sensory changes.

Additional Tests:

- Brain Imaging: Although not routinely used for diagnosis, imaging studies like MRI or DaTscan can help rule out other conditions and visualize dopamine transporter activity in the brain.

- Blood Tests: To exclude other causes of parkinsonism, such as metabolic disorders or infections.

- Genetic Testing: May be considered in cases with a strong family history or early-onset Parkinson’s disease. [8]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease primarily relies on a comprehensive clinical evaluation, incorporating a detailed medical history, neurological examination, and the exclusion of other potential causes of parkinsonism. Currently, there is no definitive laboratory test or biomarker that can confirm the diagnosis.

Key diagnostic criteria include:

- Presence of core motor symptoms: The presence of at least two of the four cardinal motor symptoms (bradykinesia, resting tremor, rigidity, and postural instability) is generally required for a diagnosis.

- Response to levodopa: A significant improvement in motor symptoms after the administration of levodopa is a strong indicator of Parkinson’s disease.

- Exclusion of other conditions: Other potential causes of parkinsonism, such as drug-induced parkinsonism, atypical parkinsonian disorders, or vascular parkinsonism, need to be ruled out through careful clinical assessment, imaging studies, and laboratory tests.

- Supportive features: The presence of additional features, such as unilateral onset, progressive course, good response to dopaminergic therapy, and the absence of atypical features, can further support the diagnosis.

Brain imaging:

- DaTscan: This imaging technique uses a radioactive tracer to visualize dopamine transporter activity in the brain. Reduced uptake in the striatum is suggestive of Parkinson’s disease, but it is not specific and can also be seen in other parkinsonian disorders.

- MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging can help rule out other structural brain abnormalities that may mimic Parkinson’s disease.

Additional Considerations:

- Early diagnosis: Early diagnosis and timely initiation of treatment are crucial for managing Parkinson’s disease effectively and improving the quality of life for individuals with the condition.

- Multidisciplinary approach: The diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease often involve a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals, including neurologists, movement disorder specialists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and mental health professionals.

- Ongoing monitoring: Regular follow-up and monitoring are essential for adjusting treatment plans, managing complications, and addressing the evolving needs of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. [9]

It is important to consult with a qualified healthcare professional for a proper diagnosis and discuss the most appropriate management options for individual cases.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis:

Essential tremor – Predominantly action tremor with symmetrical onset and response to alcohol. In detail, Positive family history may be present.

Multisystem atrophy (MSA) –

Progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized clinically by combination of parkinsonism, autonomic, cerebellar or pyramidal symptoms and signs. In general patients respond poorly to levodopa or have transient response and provide an important clue to differentiate from idiopathic PD. Urinary Incontinence and orthostatic symptoms occurring in a Parkinsonian patient within one year history of motor syndromes suggests diagnosis of MSA with high accuracy and their absence suggests PD.

Drug-induced Parkinsonism –

Neuroleptics, metoclopramide, and calcium channel blockers. Rigidity prominent but there may also be tremor, oculogyric crises, buccolingual dyspraxia and retrocollis.

Vascular Parkinsonism (VaP) –

also known as lower body parkinsonism and characterized by stepwise progression, pyramidal deficits, dementia

Alzheimer’s disease –

Early, prominent dementia, particularly with dysphasia and dyspraxia. Progressive supranuclear palsy – Early falling, eye movement abnormalities. Hydrocephalus – Urinary incontinence, greater involvement of legs than arms, early dementia.[1]

Complications

Complications:

Parkinson’s disease, while primarily a movement disorder, can lead to various complications that affect both motor and non-motor functions. These complications can significantly impact the quality of life of individuals living with the condition. Some of the most common complications include:

Motor Complications:

- Motor Fluctuations: As the disease progresses, the effectiveness of medications like levodopa may wear off before the next dose, leading to fluctuations between periods of good mobility ("on" time) and periods of increased stiffness and immobility ("off" time).

- Dyskinesia: Involuntary, jerky movements that can occur as a side effect of long-term levodopa therapy.

- Freezing of Gait: Sudden inability to move the feet while walking, often triggered by doorways or narrow spaces.

- Falls and Injuries: Impaired balance and coordination increase the risk of falls, which can lead to fractures and other injuries.

- Swallowing difficulties (Dysphagia): Muscle weakness and coordination problems can affect swallowing, increasing the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Non-motor Complications:

- Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: Dementia can develop in later stages of Parkinson’s disease, affecting memory, thinking, and judgment.

- Depression and Anxiety: Mood disorders are common in individuals with Parkinson’s disease and can further impact their quality of life.

- Sleep disturbances: Insomnia, restless leg syndrome, and REM sleep behavior disorder can disrupt sleep and contribute to daytime fatigue.

- Autonomic dysfunction: Constipation, orthostatic hypotension (drop in blood pressure upon standing), urinary problems, and sexual dysfunction can occur due to impaired autonomic nervous system function.

- Psychosis and hallucinations: Visual hallucinations and delusions can occur, particularly in those taking certain medications or with advanced disease.[10]

Investigations

Investigations:

(a) MRI usually normal. In some cases, accumulation in substantia nigra may be visualized as T2 hypersensitivity.

(b) PET – Reduced uptake in putamen. (c) SPECT – Decreased striatal metabolism

Treatment

Treatment:

The mainstay of antiparkinsonian therapy is dopamine replacement. This may be achieved either directly with levodopa or indirectly with dopamine agonists or other drugs that enhance dopaminergic transmission.

Plan of Treatment

Mild disease (Symptoms but no disability) –

(a) Selegiline from time of diagnosis. Levodopa-sparing effect of the drug delays need for levodopa therapy. When treatment becomes necessary, a dopamine agonist is added. Anticholinergics and amantadine may also be added to ward off the need for levodopa, or

(b) Levodopa 100 mg in combination with decarboxylase 25 mg t.d.s. or qds.

(c) Anticholinergic initial treatment in patients with tremor, particularly if young. With progress of the disease – Levodopa/decarboxylase inhibitor 600–800 mg, and bromocriptine 20 Mg (or Lisuride 2 mg) in 3 or 4 divided doses. Dose of levodopa and Dopamine agonists should be built up slowly.

Problems in drug treatment

Confusion and hallucinations. Levodopa is least likely to produce these complications. Anticholinergics, amantadine and selegiline should withdrawn. If these persist, dopamine agonists should minimize. If still hallucinations Nausea – Start with low doses, increased by one-half of a tablet every third day, tablet to be taken after food. Domperidone if nausea continues.

COMT inhibition i.e.

COMT inhibition (e.g. Tolcapone) is an excellent means of reducing motor fluctuations, however dyskinesias may become worse and should use with caution in these patients. persist, use Clozapine 12.5–50 mg/day. Quetiapine 25–50 mg/day. (WBC count should be monitored weekly). ECT is effective in treatment of antiparkinsonian drug-induce psychosis and improves the motor features of Parkinsonism.[1]

Postural hypotension results from a combination of the disease and the medication. If antiparkinsonian drugs cannot reduce, use fludrocortisone and midodrine.

Domperidone i.e.

Domperidone 20 mg t.d.s. sometimes reduces medication-induced hypotension. ‘On-off’ phenomenon – Late deterioration in response to L-dopa therapy may occur after 3-5 years in some patients due to loss of capacity to store dopamine (narrow therapeutic index of L-dopa). Generally, this manifests as fluctuations in response at different time of the day (on-off effect). More complex fluctuations may be in the form of hour-to-hour changes with short periods of hypokinesia, tremor and dystonia alternating with dyskinesia and agitation.

These patients should be treated with smaller more Frequent doses of levodopa (e.g. 50–100 mg q2-3h) or with addition of Selegiline (10 mg/day) to prolong and potentiate L-dopa doses.

Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation

In the form of massage and passive stretching of muscles; posture and gait training, speech therapy and occupational therapy.

Surgery

- Thalamotomy

- Deep Brain Stimulation

- Adrenal medullary foetal tissue transplantation [1]

Prevention

Prevention:

While there is no guaranteed way to prevent Parkinson’s disease, research suggests that certain lifestyle choices and interventions may lower the risk or delay the onset of the condition. These include:

Regular Exercise:

- Engaging in regular physical activity, such as aerobic exercise, strength training, and balance exercises, has been associated with a reduced risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Exercise may help protect the brain by promoting neuronal growth and survival, reducing inflammation, and improving overall health.

Healthy Diet:

- A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats may contribute to brain health and potentially lower the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Some studies suggest that specific nutrients, such as antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids, may be particularly beneficial.

Caffeine Consumption:

- Moderate caffeine intake, primarily from coffee, has been linked to a decreased risk of Parkinson’s disease. The exact mechanisms are not fully understood, but caffeine may have neuroprotective effects.

Managing Risk Factors:

- Addressing modifiable risk factors, such as avoiding exposure to pesticides and heavy metals, can also potentially reduce the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

Important Note:

- It is crucial to understand that these preventive measures do not guarantee protection against Parkinson’s disease. The development of the condition is complex and multifactorial, and more research is needed to fully understand its causes and potential preventive strategies. [11]

Homeopathic Treatment

Homeopathic medicines for Parkinson’s disease

In Honoeopathy, Homeopathic medicines are individualized, selected based on the individual case history of the patient, by taking into consideration the cause like hormonal imbalance, nutritional factor, emotional stress, the nature of the patient, and other factors which may be acting as a maintaining cause in the hair loss.

Some of the commonly prescribe remedies are as follows.

AGARICUS MUSCARIS:

This fungus contains several toxic compounds, best known is Muscarin. Agaricus acts as an intoxicant to the brain, producing more vertigo and delirium than alcohol. Jerking twitching trembling and itching are strong indications. Sensation as if pierced. Loquacity, aversion to work, indifference, fearlessness. Weakness in loins. Uncertain gait. Trembling. Trembling. Paralysis of lower limbs, with spasmodic condition of arms.

Worse – open, cold air, especially after eating, after coitus, before a thunder storm. On other hand, Better – moving about slowly.[2]

CAPSICUM:

Manifests its action mainly in chronic rheumatic, arthritic and paralytic affections, indicated by tearing, drawing pains in the muscular and fibrous tissue, with deformities about the joints; progressive loss of muscular strength, tendinous contractors. Heaviness and weakness of extremities Unsteadiness of muscles of forearm and hand. Numbness, loss of sensation in hands. Contracted tendons. Unsteady walking and easy falling. Restless legs at night. Worse – dry, cold winds, specifically, in clear fine weather, motion of carriage. Whereas Better – damp, wet weather, warmth, heat of bed.

HYOSCYAMUS:

Disturbs the nervous system profoundly. It causes a perfect picture of mania of a quarrelsome character. Weakness and nervous agitation. Tremulous weakness and twitching of tendons. In detail, Muscular twitching, spasmodic affections, generally with delirium. Picking at bedclothes, plays with hands. Besides this, Reaches out for things. Spasms also convulsions. Great restlessness; every muscle twitches. Will not be covered. Very suspicious, talkative, obscene, lascivious mania, uncovers body; jealous, foolish. Great hilarity; inclined to laugh at everything. Low, muttering speech.

Worse – night during menses, after eating, when lying down. On the other hand, Better – stooping.

PLUMBUM:

Progressive muscular atrophy. Additionally, Paralysis of single muscles. Locomotor ataxia. Cannot raise or lift anything with the hand. Extension is difficult. Pains in muscles of thighs. Comes in paroxysms. Stinging and tearing in limbs, also twitching and tingling, numbness, pain or tremor. Loss of patellar reflex. Depression. Fear of being assassinated. Quiet melancholy. Slow perception. Loss of memory. Great medicine for PD.

Worse – night, motion. On the other hand, Better – rubbing, hard pressure, physical exertion.[2]

MERCURIUS:

Tremors everywhere. Weakness with ebullitions and trembling from least exertion. Additionally, All memory symptoms are worse at night, from warmth of bed, from damp, cold, rainy weather, worse during perspiration. Complaints increase with sweat and rest; all associated with a great deal of weariness, prostration also trembling. Memory weakened and loss of will-power. Weary of life, mistrustful, thinks he is losing his reason. Weakness of limbs Oily perspiration. Trembling extremities, especially hands. Paralysis agitans.

Worse – night, wet, damp weather, lying on right side, warm room. Better – damp, wet weather, warmth, heat of bed.

PHOSPHORUS:

Irritates, inflames and degenerates mucus membranes also serous membranes, and inflames the spinal cord and nerves. Ascending sensory and motor paralysis from ends of fingers and toes. Weakness also trembling, from every exertion. Can scarcely hold anything with his hands. Arms and legs become numb. Joints suddenly give way. Oversensitive to external impressions – light, sound, odours, electrical changes, thunder storms. Loss of memory. Fidgety.

Worse – twilight, either warm food or drink, lying especially on left side, ascending stairs whereas Better – dark, lying on right side, cold food, open air, cold, sleep.

STRAMONIUM:

The entire force of this drug seems to be expended on the brain. Sensation as if limbs were separated from the body. Delirium tremens. Absence of pain and muscular mobility, especially muscles of expression and locomotion.

Rapid changes from joy to sadness. Convulsions of upper extremities and of isolated groups of muscles. Trembling, twitching of tendons. Besides this, Staggering gait.

Worse – in dark room, when alone, after sleep, on swallowing. On the other hand, Better – from company, warmth.

NOTE ALSO: CAUSTICUM, ALUMINA, AND ZINCUM METALLICUM.[2]

Diet & Regimen

Diet & Regimen of PD

- Eat at least five servings of fruits and vegetables every day. Go for those with deep, bright Color.

- Choose whole grain bread instead of white bread and choose whole grain pasta and cereals.

- Limit your consumption of red meat, including beef, pork, lamb and goat and processed meats, such as bologna and hot dogs. Fish, skinless poultry, beans, and eggs are healthier sources of protein.[3]

- choose healthful fats, such as olive oil, nuts (e.g. Almonds, walnut, pecans), Avoid partially hydrogenated fats (Trans fats) which are in many fast foods and packaged foods.

- Avoid sugar- sweetened drinks, such as soda and many fruits juice. Eat sweets as an occasional treat.

- Cut down on salt. Choose foods low in sodium by reading also comparing food labels. Besides this ,Limit the use of canned, processed, and frozen foods.

- Watch portion sizes. Eat slowly and stop eating when you are full.[3]

Do’s and Don'ts

Do’s & Don’ts

Parkinson’s Disease do’s & don’ts

Do’s:

- Stay Active: Regular exercise is crucial for managing Parkinson’s disease symptoms. Aim for at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise most days of the week. Activities like walking, swimming, cycling, dancing, and tai chi can be beneficial.

- Eat a Healthy Diet: A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can help maintain overall health and manage potential complications like constipation. Consider consulting a registered dietitian for personalized recommendations.

- Prioritize Sleep: Getting enough sleep is essential for physical and cognitive well-being. Establish a regular sleep routine and create a relaxing bedtime environment.

- Stay Connected: Social engagement and emotional support are vital for managing the challenges of Parkinson’s disease. Stay connected with friends and family, join support groups, or consider seeking professional counseling.

- Communicate with Your Healthcare Team: Maintain open communication with your doctor, neurologist, and other healthcare professionals. Discuss any changes in symptoms, medication side effects, or concerns you may have.

- Modify Your Home: Make your home environment safe and accessible by removing tripping hazards, installing grab bars, and using assistive devices as needed.

Don’ts:

- Don’t Isolate Yourself: Social withdrawal can worsen depression and anxiety. Make an effort to stay connected with others and participate in activities you enjoy.

- Don’t Neglect Your Mental Health: Depression and anxiety are common in Parkinson’s disease. Seek professional help if you experience persistent sadness, hopelessness, or anxiety.

- Don’t Skip Medications: Follow your medication schedule as prescribed by your doctor. Skipping doses can lead to worsening symptoms and complications.

- Don’t Ignore Falls: Falls are a significant risk in Parkinson’s disease. If you experience a fall, seek medical attention promptly.

- Don’t Give Up: Parkinson’s disease is a chronic condition, but it’s possible to live a fulfilling life with the right support and management strategies. [12]

Terminology

Terminology

Here are some key terminologies and their meanings that are commonly used in articles about Parkinson’s disease:

Core Motor Symptoms

- Bradykinesia: Slowness of movement and difficulty initiating movements, which can manifest in various activities such as walking, writing, or buttoning clothes.

- Rigidity: Stiffness and resistance to passive movement of the limbs and trunk.

- Resting Tremor: Involuntary shaking, typically occurring in the hands, arms, or legs at rest.

- Postural Instability: Impaired balance and coordination, leading to an increased risk of falls.

Non-motor Symptoms

- Cognitive Impairment: Problems with attention, memory, and executive functions, potentially leading to dementia in advanced stages.

- Depression and Anxiety: Mood disturbances, often associated with the challenges of living with a chronic illness.

- Sleep Disturbances: Insomnia, restless leg syndrome, and REM sleep behavior disorder.

- Autonomic Dysfunction: Constipation, orthostatic hypotension (drop in blood pressure upon standing), urinary problems, and sexual dysfunction.

- Hyposmia: Reduced sense of smell, often an early sign of Parkinson’s disease.

Pathological Terms

- Lewy Bodies: Abnormal protein aggregates primarily composed of alpha-synuclein, found within neurons in Parkinson’s disease and associated with neuronal dysfunction and death.

- Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta: A region of the brain crucial for movement control, where dopaminergic neurons are progressively lost in Parkinson’s disease.

- Dopamine Depletion: Reduction in dopamine levels in the brain due to the loss of dopaminergic neurons, leading to motor and non-motor symptoms.

- Neuroinflammation: Activation of microglia and astrocytes, the brain’s immune cells, leading to the release of inflammatory molecules that can damage neurons.

- Oxidative Stress: Increased production of reactive oxygen species and impaired antioxidant defenses, causing damage to cellular components and contributing to neuronal death.

Treatment-Related Terms

- Levodopa: A medication that is converted to dopamine in the brain, used to manage motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease.

- Dopamine Agonists: Medications that mimic the action of dopamine in the brain.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS): A surgical procedure involving the implantation of electrodes in the brain to deliver electrical stimulation, helping to manage motor symptoms.

- Motor Fluctuations: Fluctuations in motor function between periods of good mobility ("on" time) and periods of increased stiffness and immobility ("off" time), often seen in advanced stages of the disease.

- Dyskinesia: Involuntary, jerky movements that can occur as a side effect of long-term levodopa therapy.

Other Important Terms

- Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease: The most common type of Parkinson’s disease, with no known specific cause.

- Atypical Parkinsonian Disorders: A group of neurodegenerative conditions that share some features with Parkinson’s disease but often progress more rapidly and respond less well to treatment.

- Parkinsonism: A broader term encompassing various conditions that present with similar symptoms to Parkinson’s disease, including primary and secondary parkinsonism.

Here are some common terminologies and their meanings used in homeopathic articles about Parkinson’s disease:

Core Symptoms & Related Terms:

- Bradykinesia: Slowness of movement; difficulty initiating voluntary movements.

- Tremor: Involuntary shaking, typically at rest; may worsen with stress or fatigue.

- Rigidity: Stiffness or inflexibility of muscles, often described as a feeling of tightness.

- Postural Instability: Impaired balance and coordination, leading to difficulty maintaining an upright posture and increased risk of falls.

- Festination: Short, shuffling steps and a tendency to accelerate while walking, making it difficult to stop or change direction.

- Micrographia: Small, cramped handwriting, often a result of bradykinesia and rigidity.

- Hypomimia: Reduced facial expression, often described as a "mask-like" face.

- Hypophonia: Soft, monotonous speech, often with reduced volume and clarity.

Non-motor Symptoms & Related Terms:

- Anxiety: Feelings of worry, nervousness, or unease.

- Depression: Persistent sadness, hopelessness, or loss of interest in activities.

- Constipation: Infrequent bowel movements or difficulty passing stool.

- Insomnia: Difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep.

- Fatigue: Persistent tiredness or lack of energy.

- Cognitive Impairment: Problems with memory, attention, or decision-making.

Homeopathic Concepts & Remedies:

- Miasm: A predisposing constitutional weakness or tendency towards certain types of diseases.

- Totality of Symptoms: The complete picture of the patient’s physical, mental, and emotional symptoms, used to select the most appropriate homeopathic remedy.

- Individualization: The process of selecting a remedy based on the unique characteristics and symptom presentation of each patient.

- Potency: The degree of dilution and succussion (vigorous shaking) of a homeopathic remedy, believed to influence its strength and depth of action.

- Aggravation: A temporary worsening of symptoms after taking a remedy, often considered a positive sign indicating the remedy is working.

- Amelioration: An improvement in symptoms after taking a remedy.

- Repertory: A reference book listing symptoms and the remedies associated with them, used to aid in remedy selection.

- Materia Medica: A collection of detailed descriptions of the properties and effects of homeopathic remedies.

Some Commonly Mentioned Homeopathic Remedies for Parkinson’s:

- Zincum Metallicum: For restlessness, fidgeting, and trembling, particularly in the extremities.

- Plumbum Metallicum: For slowness of movement, muscle weakness, and constipation.

- Causticum: For rigidity, muscle cramps, and difficulty swallowing.

- Mercurius Vivus: For tremors, restlessness, and excessive salivation.

References

Reference

- Text Book of Medicine Golwala

- Homoeopathic Body-System Prescribing – A Practical Workbook of Sector

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/mens-health/10-diet-and-exercise-tips-for-prostate-health]

- Book Title: "Parkinson’s Disease & Movement Disorders", Edition: 7th Edition Authors: Stewart A. Factor, William J. Weiner, Year of Publication: 2018 ,Publisher: Elsevier

Book Title: "Brain & Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Neuroscience" Edition: 6th Edition

Authors: Bob Garrett, Gerald Hough, Year of Publication: 2021

Publisher: SAGE Publications, Inc.Book Title: Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects

Editors: Timothy J. Collier, Glenda M. Halliday, and Per Svenningsson

Year of Publication: 2019

Publisher: Academic PressBook Title: "Merritt’s Neurology"

Edition: 14th Edition Author: Lewis P. Rowland, Timothy A. Pedley

Year of Publication: 2021

Publisher: Wolters KluwerBook Title: "Neurological Differential Diagnosis: A Case-Based Approach" Edition: 2nd Edition

Authors: Alan J. Lerner, Alejandro A. Rabinstein, Year of Publication: 2016, Publisher: Cambridge University PressBook Title: "Movement Disorders: 100 Instructive Cases", Edition: 1st Edition, Authors: Werner Poewe, Günther Deuschl, Year of Publication: 2010, Publisher: Cambridge University Press

Book Title: "Parkinson’s Disease: A Complete Guide for Patients and Families", Edition: 4th Edition

Author: Rajesh Pahwa, Year of Publication: 2021, Publisher: Johns Hopkins University PressBook Title: "Ending Parkinson’s Disease: A Prescription for Action"

Authors: Ray Dorsey, Michael S. Okun, Todd Sherer, Bastiaan R. Bloem, Year of Publication: 2020

Publisher: PublicAffairsBook Title: "Parkinson’s Disease: The Complete Guide to Symptoms, Treatments, and Living Well"

Edition: 2nd Edition, Author: Aparna Wagle Shukla, Year of Publication: 2019, Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Also Search As

Also Search As:

People can search for homeopathic articles on Parkinson’s disease using a variety of online and offline resources. Here are some effective methods:

Online:

Search engines:

Use popular search engines like Google, DuckDuckGo, or Bing.

Use specific keywords: "Parkinson’s disease homeopathy", "homeopathic treatment Parkinson’s", "homeopathy for Parkinson’s symptoms", etc.

Include additional terms to refine the search: "case studies", "research articles", "clinical trials", "homeopathic remedies Parkinson’s", etc.

Homeopathic journals and websites:

Search websites of reputed homeopathic journals like "The Homoeopathic Journal", "The Indian Journal of Research in Homoeopathy" or websites of homeopathic organizations for articles specifically focused on Parkinson’s.

Online databases:

Explore online databases like PubMed or Google Scholar, using similar search terms mentioned earlier. Some articles may require a subscription or payment to access the full text.

Social media and forums:

Search relevant groups and communities on platforms like Facebook or Reddit where people share homeopathic information and experiences.

Offline:

Libraries:

Visit local libraries or specialized medical libraries to access homeopathic journals, books, and other resources.

Homeopathic clinics and practitioners:

Consult with experienced homeopathic practitioners who may have access to relevant articles or case studies.

Bookstores:

Look for books on homeopathy with sections on Parkinson’s disease or neurological conditions.

Important Considerations:

Credibility and reliability:

Evaluate the source of the information. Prioritize articles from reputable homeopathic journals, peer-reviewed research, and qualified practitioners.

Evidence-based approach

: While exploring homeopathic information, remember that the scientific evidence for homeopathy in Parkinson’s is limited. Consider consulting with conventional medical professionals alongside any homeopathic treatment.

Individualization:

Homeopathy emphasizes individual treatment plans. Avoid self-prescribing remedies based solely on articles. Consult with a qualified homeopath for personalized assessment and treatment.

There are numerous ways to search for information about Parkinson’s disease, utilizing both online and offline resources. Here’s a breakdown of some common methods:

Online Search Methods:

Search Engines:

Utilize popular search engines like Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, etc.

Employ specific keywords like:

- "Parkinson’s disease"

- "Parkinson’s symptoms"

- "Parkinson’s treatment"

- "Parkinson’s research"

Refine your search by including additional terms such as:

- "causes of Parkinson’s"

- "stages of Parkinson’s"

- "living with Parkinson’s"

- "Parkinson’s support groups"

- Specific names of medications or therapies

Reputable Websites:

Visit websites of established health organizations:

- National Institutes of Health (NIH)

- Mayo Clinic

- Parkinson’s Foundation

- Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research

- World Health Organization (WHO)

These websites typically provide reliable, evidence-based information about the disease, its symptoms, treatment options, and ongoing research.

Medical Journals & Databases:

If you require more in-depth, scientific information, access medical journals and databases like:

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- ScienceDirect

Search for articles, clinical trials, and research studies using keywords related to Parkinson’s disease.

Social Media & Online Communities:

Join online forums and support groups on platforms like Facebook, Reddit, or specialized Parkinson’s disease communities.

These can be valuable resources for connecting with others affected by Parkinson’s, sharing experiences, and getting emotional support.

Offline Search Methods:

Libraries:

Visit your local library or a medical library to access books, journals, and other resources on Parkinson’s disease.

Librarians can assist you in finding relevant materials.

Healthcare Professionals:

Consult your doctor, neurologist, or other healthcare providers for information about Parkinson’s disease.

They can answer your specific questions, provide personalized guidance, and recommend further resources.

Support Groups & Organizations:

Attend meetings or events organized by local or national Parkinson’s disease support groups and organizations.

These provide opportunities to connect with others affected by the disease, learn about the latest research, and access resources and support services.

Remember:

Always prioritize information from reliable sources.

Be critical of online information, especially on social media or unverified websites.

If you have any concerns about Parkinson’s disease, consult with a qualified healthcare professional.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Parkinson's disease?

Definition:

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects movement, primarily caused by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain.

What causes Parkinson's disease?

The exact cause is unknown, but

It is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Is there a cure for Parkinson's disease?

Currently, there is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, but various medications and therapies can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

What are the early signs of Parkinson's disease?

Early signs may include:

Tremors, slowness of movement, muscle stiffness, changes in posture or balance, and subtle changes in speech or writing.

Can homeopathy help with Parkinson's disease?

Homeopathy aims to stimulate the body’s natural healing abilities to manage symptoms and potentially slow disease progression.

How does homeopathic treatment differ from conventional treatment for Parkinson's?

Homeopathy focuses on the whole person and their unique symptom picture, aiming to address the underlying imbalances.

Conventional treatment primarily uses medications to manage symptoms.

What are the treatment options for Parkinson's disease?

Treatment options include

Medications to replace or mimic dopamine, deep brain stimulation surgery, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

Is there scientific evidence supporting homeopathy for Parkinson's?

Research on homeopathy for Parkinson’s is limited, and its effectiveness is debated.

Some studies show positive results, but more rigorous research is needed.

How do I find a qualified homeopath for Parkinson's disease?

Seek a registered homeopath with experience in treating neurological conditions. You can search online directories or ask for recommendations from trusted sources.

What homeopathic remedies are commonly used for Parkinson's disease?

Homeopathic medicine for Parkinson’s disease:

Remedies like Zincum metallicum, Plumbum metallicum, and Causticum are often considered, but a qualified homeopath will individualize treatment based on the specific symptoms.