Deliberate Self-harm

Definition

Deliberate self-harm is not usually fail suicide. Only about a quarter of those who have deliberately harmed themselves say they wished to die; most say the act was impulsive rather than premeditated.

The rest find it difficult to explain the reasons or say that:

They were seeking unconsciousness as a temporary escape or relief from their problems;

They were trying to influence another person to change their behaviour (e.g. to make a partner feel guilty about threatening to end the relationship);

Patient are uncertain whether or not they intended to die they were ‘leaving it to fate’.

Here are some synonyms of suicide. Some less direct options you might consider:

- Self-harm

- Ending one’s life

- Taking one’s own life

If you are thinking about suicide, please know that help is available. You can call a suicide hotline or mental health professional. Here are some resources that can help:

- India: Lifeline – 1036 (toll-free)

- International Association for Suicide Prevention

You are not alone. There are people who care about you and want to help.

Overview

Methods

Epidemiology

Causes

Types

Risk Factors

Pathogenesis

Pathophysiology

Clinical Features

Sign & Symptoms

Clinical Examination

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Complications

Investigations

Treatment

Prevention

Homeopathic Treatment

Diet & Regimen

Do’s and Don'ts

Terminology

References

Also Search As

Overview

Overview

Deliberate self-harm is common and rates have risen progressively over the last 30 years.

It now accounts for about 10 percent of acute medical admissions in the UK.

A further smaller number are see by general practitioners but not sent to hospital because the medical risks are low, or attend emergency departments but are not admitted.

Epidemiological studies have shown the kind of people who are more likely to harm themselves and the methods that are common.

Deliberate self-harm is more common among:

- younger adults: the rates decline sharply during adult life (they are also very low in children under the age of 12 years);

- young women, particularly those aged 15–20 years;

- people of low socioeconomic status;

- divorced individuals, teenage wives, and younger single adults. [1]

Methods

Methods

Drug Overdose:

- In the UK, about 90 percent of the cases of deliberate self-harm treated by general hospitals involve drug overdose.

- The drugs taken most commonly in overdose are anxiolytics, non-opiate analgesics, such as salicylates and paracetamol, and antidepressants.

- Paracetamol is particularly dangerous because it damages the liver and may lead to delayed death, sometimes in patients who had not taken the drugs with the intention of dying.

- Antidepressants are take in about a fifth of cases.

- Of these drugs, tricyclics are particularly hazardous in overdosage since they may cause cardiac arrhythmias or convulsions.

- Despite these and other dangers, most deliberate drug overdoses do not present a serious threat to life.

The use of alcohol:

- About half of the men and a quarter of the women who harm themselves have taken alcohol within 6 hours before the act.

- This often precipitates the act by reducing self-restraint.

- Lastly, Its effects interact with those of the drugs.

Self Injury:

- In the UK, between 5 and 15 percent of all cases of deliberate self-harm treat in general hospitals are self-inflicted injuries.

- Moreover, Most of these injuries are lacerations, usually of the forearm or wrist.

- Most patients who cut themselves are young, have low self-esteem, impulsive or aggressive behaviour, unstable moods, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, also often problems of either alcohol or drug abuse.

- Basically, the self-laceration follows a period of increasing tension and irritability which is relieve by the self-injury.

- Besides this, The cuts are usually multiple and superficial, often made with a razor blade or a piece of glass.

- All in all, These highly dangerous acts occur mainly among people who intended to die but have survived.

Less frequent and medically more serious forms of self injury i.e.:

- Deeper lacerations,

- Jumping from heights

- Jumping in front of a either moving train or motor vehicle

- Shooting

- Drowning

- Burning [1]

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of deliberate self-harm (DSH) in India is a complex and evolving issue. Studies have shown varying prevalence rates and patterns of DSH across different regions and populations.

One significant study is "Deliberate self-harm in India: A systematic review" by Patel et al., published in 2012. This review synthesized findings from multiple studies and highlighted the following key points:

Prevalence: The prevalence of DSH in India ranged from 0.2% to 34.4% across different studies, with higher rates reported in certain populations like young adults and women.

Methods: Common methods of DSH in India included poisoning (especially with pesticides), self-cutting, and hanging.

Risk factors: Identified risk factors for DSH included mental disorders (like depression and anxiety), interpersonal conflicts, and socioeconomic stressors.

It’s important to note that this study is a systematic review and the data may vary depending on the individual studies included.

For more recent data, it is recommended to search for newer publications on the topic. It is also important to consider that the COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced the patterns of DSH in India. [2]

Causes

Causes

Deliberate self-harm is usually the result of multiple social and personal factors, including national and local attitudes.

Overall, rates appear to be affected by awareness of the occurrence and methods of self-harm in a population (for example, television and press reports and local knowledge of suicide and attempted suicide in the neighbourhood).

Some causes of deliberate self-harm:

- Psychiatric disorder

- Personality disorder

- Alcohol dependence

- Predisposing social factors

- Early parental loss

- Parental neglect or abuse

- Long-term social problems: e.g. family, employment, financial

- Poor physical health

- Precipitating social factors

- Stressful life problems

Social and family factors:

Predisposing factors such as:

- Basically, Evidence of childhood emotional deprivation is common.

- Many patients who harm themselves have long-term marital problems, extramarital relationships, or other relationship problems, also may have financial and other social difficulties.

- Lastly, Rates of unemployment are greater than in the general population.

Precipitating factors such as:

- Stressful life events are frequent before the act of self-harm, especially quarrels with or threats of rejection by spouses or sexual partners.

Association with psychiatric disorder:

- Although many patients who harm themselves are anxious or depressed, relatively few have a psychiatric disorder other than an acute stress reaction, adjustment disorder, or personality disorder.

- The latter is found in about a third to a half of self-harm patients, and dependence on alcohol is also frequent. (In contrast, psychiatric disorder is common among patients who die by suicide.) [1]

Types

Types of Deliberate Self-harm

- Cutting: The most prevalent form of DSH, often involving using sharp objects to create superficial wounds on the skin.

- Burning: Deliberately inflicting burns using cigarettes, lighters, or other hot objects.

- Scratching: Intentional and repeated scratching of the skin to cause injury.

- Hitting or bruising: Self-inflicted physical harm through punching or striking oneself.

- Poisoning: Ingesting harmful substances or overdosing on medication.

- Hair-pulling: Recurrent pulling out of one’s hair, resulting in noticeable hair loss.

This is not an exhaustive list, as individuals may engage in other forms of self-harm not mentioned here. Additionally, the book emphasizes that the reasons behind DSH are complex and multifaceted, often serving as a way to cope with emotional distress or communicate underlying psychological pain. [3]

Risk Factors

Risk factors of Deliberate Self- harm

Various risk factors associated with deliberate self-harm (DSH) are identified:

Individual Factors:

- Mental health conditions: Individuals with depression, anxiety, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, and substance abuse disorders are at a higher risk.

- Previous history of trauma: Experiences of abuse, neglect, or other traumatic events increase vulnerability.

- Low self-esteem and negative self-image: Feeling inadequate or worthless can contribute to self-harming behaviors.

- Impulsivity and poor emotional regulation: Difficulty managing intense emotions or acting impulsively can lead to DSH.

Social Factors:

- Social isolation and lack of support: Feeling disconnected or unsupported can increase the risk.

- Exposure to self-harm in others: Witnessing or learning about self-harm in peers or through media can normalize the behavior.

- Bullying or interpersonal conflict: Experiencing bullying or strained relationships can contribute to emotional distress and DSH.

Environmental Factors:

- Stressful life events: Major life changes, losses, or academic pressures can trigger DSH.

- Access to means of self-harm: Easy access to sharp objects, medications, or other harmful substances can increase the likelihood of DSH.

It’s important to note that these are just some of the risk factors, and the presence of one or more does not guarantee that someone will engage in self-harm. Understanding these risk factors can aid in prevention and early intervention efforts. [3]

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis of Deliberate Slef- harm

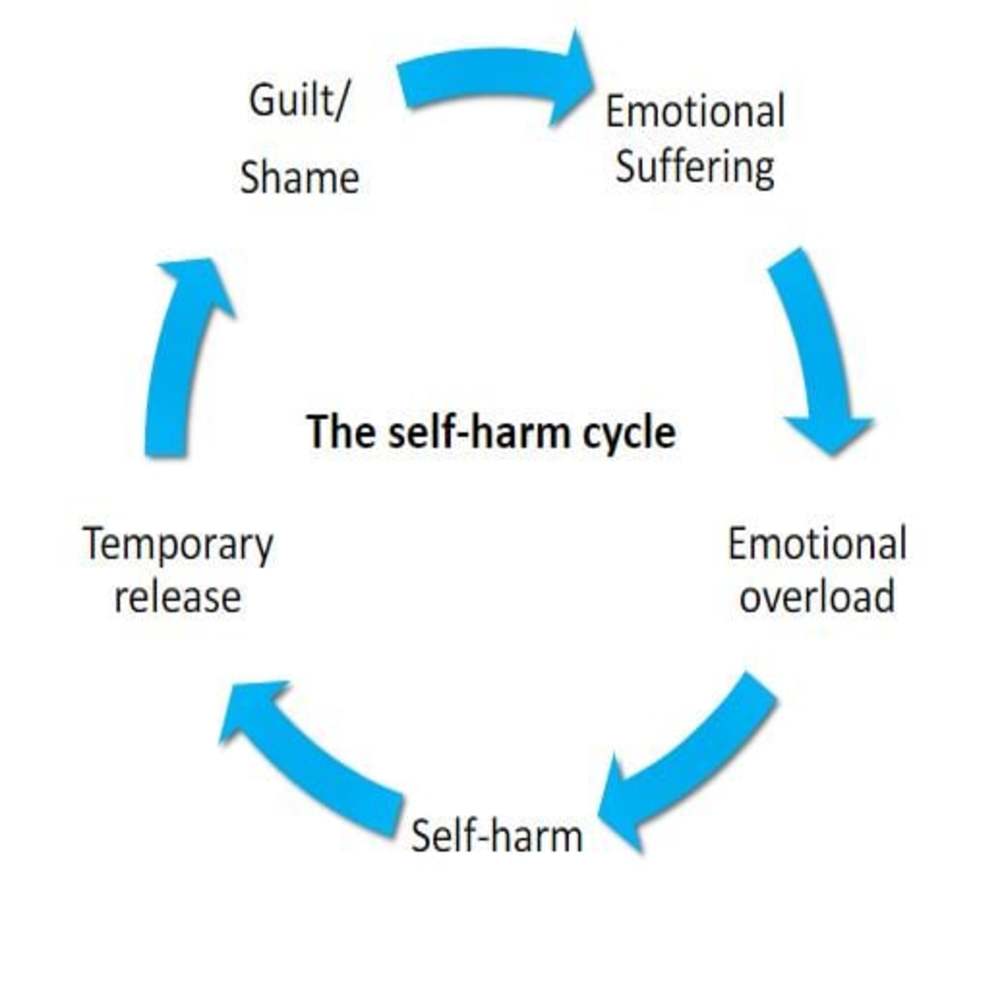

Emotion Regulation Model: This model posits that individuals engage in DSH as a maladaptive way to regulate intense negative emotions. Self-harm may provide temporary relief from emotional pain or numbness by activating competing physical sensations.

Social Signaling Model: This model suggests that DSH serves as a way to communicate distress or elicit help from others. The self-inflicted injuries can be seen as a visible sign of internal suffering, prompting others to offer support or intervention.

Self-Punishment Model: In this model, DSH is viewed as a form of self-punishment or self-hatred. Individuals may engage in self-harm to alleviate feelings of guilt, shame, or worthlessness.

Experiential Avoidance Model: This model proposes that DSH is a way to avoid or escape from unwanted thoughts, feelings, or memories. Self-harm may provide a temporary distraction from internal distress, albeit at a significant physical cost.

Neurobiological Model: This model highlights the role of neurotransmitters and brain regions involved in pain processing, emotional regulation, and impulsivity. Dysregulation in these systems may contribute to the vulnerability to engage in DSH.[3]

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology of Deliberate self-harm

Neurobiological Factors:

- Pain Perception and Regulation: Individuals who engage in DSH may have altered pain perception or pain-regulating mechanisms. Studies have shown differences in endogenous opioid activity and responses to painful stimuli in individuals with a history of self-harm.

- Serotonin and Dopamine Systems: Dysregulation in these neurotransmitter systems, which are involved in mood regulation, impulsivity, and aggression, has been implicated in DSH.

- Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis: This stress response system may be hyperactive in individuals who self-harm, contributing to heightened emotional reactivity and difficulty managing stress.

Psychological Factors:

- Emotional Dysregulation: Difficulty identifying, expressing, and regulating emotions effectively is a key factor in DSH. Individuals may experience intense emotional pain and lack healthy coping mechanisms to manage it.

- Cognitive Distortions: Negative thoughts and beliefs about oneself, the world, and the future can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness, increasing the risk of self-harm.

- Dissociation: Some individuals may experience dissociation during or after self-harm, a detachment from reality or a numbing of emotions, which can reinforce the behavior.

Environmental and Social Factors:

- Early Life Adversity: Experiences of trauma, abuse, or neglect can disrupt healthy development and increase vulnerability to DSH.

- Social Isolation and Rejection: Feeling disconnected from others and lacking social support can contribute to feelings of loneliness and despair, leading to self-harm.

- Exposure to Self-Harm: Witnessing or learning about self-harm in others can normalize the behavior and increase the risk of engaging in it. [3]

Clinical Features

Clinical Features of DSH

Physical Signs:

- Visible injuries: Cuts, burns, bruises, or scars on the skin are often the most apparent signs.

- Location of injuries: Commonly found on accessible areas like the arms, legs, or abdomen.

- Pattern of injuries: May be repetitive or clustered in a specific area, indicating habitual self-harm.

- Other physical symptoms: Depending on the method used, individuals may experience poisoning symptoms, hair loss, or other physical complications.

Psychological and Behavioral Signs:

- Emotional distress: Individuals may exhibit depression, anxiety, irritability, or emotional numbness.

- Secretive or ashamed behavior: Often trying to hide injuries or avoid discussing self-harm.

- Changes in mood or behavior: Sudden withdrawal, isolation, or increased irritability can be indicative.

- Difficulty coping with stress: May turn to self-harm as a way to manage overwhelming emotions.

Social and Interpersonal Signs:

- Relationship problems: Difficulty maintaining healthy relationships or experiencing conflict with others.

- Social isolation: Withdrawing from social activities or avoiding interactions with friends and family.

- Feeling misunderstood or invalidated: May feel that others do not understand their pain or struggles. [3]

Sign & Symptoms

Sign & Symptoms

Physical Signs:

- Scars: These are often the most visible signs of self-harm and can be located on the arms,legs, or torso.

- Fresh cuts, burns, or bruises: These may be present on the skin and can vary in severity depending on the method used.

- Bandages or dressings: Individuals may use bandages to cover up injuries.

- Wearing long sleeves or pants in warm weather: This might be an attempt to hide signs of self-harm.

Behavioral Signs:

- Withdrawal or isolation from friends and family: Self-harming individuals may withdraw from social interactions.

- Changes in mood or behavior: Increased irritability, sadness, or anxiety can be signs of emotional distress.

- Expressing feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness: These feelings can be indicators of underlying mental health issues.

- Talking about self-harm or suicide: This should always be taken seriously and addressed with professional help. [3]

It’s important to note that not everyone who self-harms will exhibit all of these signs and symptoms. If you are concerned that someone you know may be self-harming, it’s important to reach out and offer support. Encourage them to seek professional help from a mental health professional.

Clinical Examination

Clinical Examination of Deliberate self-harm

A comprehensive approach to clinical examination is outlined:

Physical Examination:

- Thorough inspection of injuries: Noting the type, location, size, and depth of wounds.

- Assessing for signs of infection or complications: Checking for redness, swelling, pus, or fever.

- Evaluating for medical risks: Determining if immediate medical attention is required.

Psychological Assessment:

- Mental status examination: Assessing mood, affect, thought content, and cognitive function.

- Screening for psychiatric disorders: Identifying potential underlying conditions like depression, anxiety, or personality disorders.

- Evaluating suicide risk: Determining the level of risk for self-harm and suicidal ideation.

Psychosocial Assessment:

- Exploring the function of self-harm: Understanding the reasons behind the behavior, such as emotional regulation, communication, or self-punishment.

- Assessing social support and coping skills: Identifying sources of support and evaluating the individual’s ability to manage stress and emotions.

- Reviewing past trauma or adverse experiences: Exploring potential triggers for self-harm and identifying any unresolved trauma.

Additional Assessments:

- Laboratory tests: May be necessary to rule out medical conditions or assess for substance use.

- Imaging studies: Rarely needed unless there are concerns about internal injuries. [3]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Assessment:

In General, Every act of deliberate self-harm should be assessed thoroughly.

In detail, For many patients seen in primary care, the physical consequences of the act and concern about the risk of repetition will lead to hospital referral.

Besides this, All deliberate self-harm patients seen in hospital emergency departments should have a psychiatric and social assessment.

All in all, Since many patients who are medically fit do not wish to stay for specialist assessment, it is essential that all emergency department medical staff are competent to assess risk.

Steps in assessment:

- The assessment should carry out in a way that encourages patients to undertake a constructive review of their problems and of the ways they can deal with them.

- If patients can then resolve their problems in this way, they may able to do so again in the future instead of resorting to self-harm again.

When to assess:

- When patients have recovered sufficiently from the physical effects of the self-harm they should interview, if possible, where the discussion will not be overheard or interrupted.

- After a drug overdose, the first step is to determine whether consciousness is impaired.

Sources of information:

- Information should obtain also from relatives or friends, the general practitioner, and any other person (such as a social worker) already involved in the patient’s care.

Information Required:

1. What were the patient’s intentions before and at the time of the attempt ?

Patients whose behaviour suggests that they intended to die as a result of the act of self harm are at greater risk of a subsequent fatal act of self-harm.

Intent is assess by considering the following:

- Was the act planned or carried out on impulse ?

- Were precautions taken against being found ?

- Did the patient seek help after the act ?

- Was the method dangerous ?Not only should the objective risk be assessed, but also the risk anticipated by the patient, which may be different (e.g. if he believed that he had taken a lethal dose of a drug even though he had not).

- Was there a ‘final act’ such as writing a suicide note or making a will?

2. Does the patient now wish to die ?

- The interviewer should ask directly whether the patient is relieved to have recovered or wishes to die.

- If the act suggested serious suicidal intent, but the patient denies such intent, the interviewer should try to find out by tactful but thorough questioning whether there has been a genuine change of resolve.

3. What are the current problems ?

- Many patients will have experienced a mounting series of difficulties in the weeks or months leading up to the act of self-harm.

- Some of these difficulties may have resolved by the time the patient is interviewed, but if serious problems remain, the risk of a fatal repetition is greater.

- This risk is particularly great if the problems are of loneliness or ill health.

- Possible problems should review systematically, covering intimate relationships with the spouse or another person, relations with children and other relatives, employment, finance, and housing, legal problems, social isolation, bereavement, and other losses.

4. Is there any psychiatric disorder ?

- This question is answer with information obtained from the history, from a brief but systematic examination of the mental state, and also from other informants and from medical notes.

5. What are the patient’s resources ?

- These include the capacity to solve problems, material resources, and the help that others may provide.

- The best guide to future ability to solve problems is the past record of dealing with difficulties such as the loss of a job, or a broken relationship.

- The availability of help should be assessed by asking about the patient’s friends and relatives, and about support available from medical services, social workers, or voluntary agencies.

6. Is treatment required and will the patient agree to it ?

Management aims to i.e.:

- Treat any psychiatric disorder;

- Manage high suicide risk;

- Enable the patient to resolve difficulties that led to the act of self-harm;

- Deal with future crises without resorting to self-harm. [1]

Differential Diagnosis

Difference between suicide & deliberate self-harm:

| Suicide | Deliberate self-harm | |

Age | Older | Younger |

Sex | More often male | More often female |

Psychiatric disorder | Common, severe | Less common, less severe |

Physical illness | Common | Uncommon |

Planning | Careful | Impulsive |

Method | Lethal | Less dangerous |

Complications

Complications of Deliberate Self Harm

Some potential complications include:

Physical Complications:

- Infection: Wounds from self-harm can become infected, leading to pain, swelling, and potentially serious medical complications.

- Scarring: Repeated self-harm can result in permanent scarring, which can be a source of distress for some individuals.

- Functional impairment: Severe injuries can lead to loss of function or disability, depending on the location and extent of the damage.

- Medical complications: Specific methods of self-harm can lead to specific complications, such as organ damage from poisoning or respiratory problems from smoke inhalation.

Psychological Complications:

- Increased risk of suicide: While not all individuals who self-harm are suicidal, DSH is a significant risk factor for future suicide attempts.

- Shame and guilt: Self-harm can lead to feelings of shame, guilt, and self-loathing, which can further exacerbate mental health problems.

- Social isolation: Individuals who self-harm may withdraw from social interactions due to fear of judgment or stigma.

- Reinforcement of self-harm cycle: Repeated self-harm can create a maladaptive coping mechanism, making it more difficult to break the cycle.

Social and Interpersonal Complications:

- Relationship difficulties: Self-harm can strain relationships with family, friends, and romantic partners.

- Stigma and discrimination: Individuals who self-harm may face stigma and discrimination in various settings, including healthcare and employment.

- Social isolation and loneliness: Stigma and shame can lead to social isolation, further increasing the risk of mental health problems. [3]

Investigations

Investigations of Deliberate self – harm

Physical Investigations:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): To assess for anemia or signs of infection.

- Blood Chemistry: To check for electrolyte imbalances or organ dysfunction, especially if there is a history of substance ingestion.

- Toxicology Screen: To identify any drugs or substances that may have been used in the self-harm act.

- Coagulation Studies: To assess for bleeding disorders, especially if there is excessive bleeding from wounds.

- Imaging Studies: X-rays or CT scans may be indicated if there are concerns about internal injuries or fractures.

Psychological Investigations:

- Clinical Interview: A thorough assessment of the individual’s mental state, including mood, anxiety, thought content, and suicidal ideation.

- Psychometric Assessments: Standardized questionnaires or scales can be used to assess depression, anxiety, personality disorders, and other relevant psychological factors.

- Neuropsychological Assessment: In some cases, tests of cognitive function, attention, and memory may be helpful to rule out any neurological contributions to the behavior. [3]

Treatment

Treatment

Management:

Generally, The patient is encourage to consider what steps he could take to resolve each of these problems, also to formulate a practical plan for tackling one at a time.

Furthermore, Throughout this discussion, the therapist helps the patient to do as much as possible to help himself.

At Last, When there are interpersonal problems, it is often helpful to have a joint or family discussion.

The results of treatment:

- Successful treatment of a depressive or other psychiatric disorder reduces the risk of subsequent self-harm.

- There is less strong evidence that problem solving and other psychological methods reduce repetition, although they do reduce personal and social problems.

- This lack of strong evidence may due, in part, to the methodological difficulties of randomized trials in this heterogeneous population.

- Particular types of psychological or social problem have shown to benefit from specific treatments, such as couple therapy for problems between couples, problem solving for practical and everyday difficulties, and cognitive behaviour treatment for longstanding personal difficulties.

Management of special groups:

Certain subgroups of patients pose special management problems. In most cases, specialist advice should obtain.

Mothers of young children:

- Because there is an association between deliberate self-harm and child abuse, it is important to ask any mother with young children about her feelings towards the children, and to enquire from other informants, as well as the patient, about their welfare.

- If there is a possibility of child abuse or neglect, appropriate assessment action should be carried out.

- There is also an association between depression and infanticide.

Children and adolescents:

- Deliberate self-harm is uncommon among young children, but becomes increasingly frequent after the age of 12, especially among girls.

- The most common method is drug overdose; in only a few cases is there a threat to life.

- The motivation for self-harm in young children is difficult to determine, but it is more often to communicate distress or escape from stress than to die.

- Deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents is associate with broken homes, family psychiatric disorder, and child abuse.

- It is often precipitate by difficulties with parents, boyfriends or girlfriends, or schoolwork.

- Most children and adolescents do not repeat an act of deliberate self-harm, but an important minority do so, usually in association with severe psychosocial problems.

- These repeated acts of deliberate self-harm carry a significant risk of suicide.

- Children or adolescents who harm themselves should be assessed by a child psychiatrist.

- Treatment is not only of the young person but also of the family.

Patients who refuse assessment and treatment:

- Generally, In most countries, there is a legal power to detain those who require potentially life-saving treatment also whose competence or capacity to take an informed decision about discharge is likely to be impaired by their mental state.

- Besides this, The doctor should obtain as much information about mental state also suicidal risk as time allows.

- The patient should only be allowed to leave hospital when serious suicidal risk has been excluded.

- In taking decisions about emergency treatment, the doctor is likely to be helped by relatives, additionally; inpatient medical notes, also by telephoning the primary care doctor, social worker, or person who has been involved with the patient in the past.

- It is essential to write detailed notes and to be aware of the legal requirements about both emergency treatment and confidentiality.

Frequent repeaters:

- Some people take overdoses repeatedly, often at times of stress in circumstances that suggest that the behaviour is to either reduce tension or gain attention.

- Furthermore, These people usually have a personality disorder also many insoluble social problems.

- Although sometimes directed towards gaining attention, repeated self-harm may cause relatives to become unsympathetic or hostile, and these feelings may be shared by professional staff as their repeated efforts at help are seen to fail.

- Neither counselling nor intensive psychotherapy is effective, and management is limited to providing support.

- Sometimes a change in life circumstances is followed by improvement, but unless this happens the risk of death by suicide is high.

Deliberate self-laceration:

- It is difficult to help people who lacerate themselves repeatedly.

- They often have low self-esteem and experience extreme tension.

- Efforts should be made to increase self-esteem and to find an alternative, simple way of relieving tension, for example, by taking exercise.

- Anxiolytic drugs are seldom helpful and may produce disinhibition.

- Lastly, If drug treatment is needed to reduce tension, a phenothiazine is more likely to be effective. [1]

Prevention

Prevention

Universal Prevention:

- Promoting mental health literacy: Educating the public about mental health, recognizing warning signs, and seeking help.

- Reducing stigma: Creating a supportive and accepting environment for individuals struggling with mental health issues.

- Enhancing coping skills and resilience: Teaching individuals healthy ways to manage stress, emotions, and interpersonal difficulties.

- Restricting access to means of self-harm: Limiting access to potentially harmful objects or substances.

Selective Prevention:

- Targeting high-risk groups: Focusing on individuals with known risk factors, such as those with a history of trauma, mental illness, or previous self-harm.

- Early intervention programs: Providing early identification and support for individuals showing signs of distress or self-harm.

- School-based prevention programs: Implementing programs that address bullying, social isolation, and teach coping skills.

Indicated Prevention:

- Individualized interventions: Providing therapy, counseling, and medication for individuals who have already engaged in self-harm.

- Family-based interventions: Involving family members in treatment and providing support to address family dynamics that may contribute to self-harm.

- Safety planning: Developing a plan with the individual to help them cope with urges to self-harm and access support when needed. [3]

Homeopathic Treatment

Homeopathic Treatment for Deliberate Self- harm

Homeopathy treats the person as a whole. It means that homeopathic treatment focuses on the patient as a person, as well as his pathological condition. The homeopathic medicines selected after a full individualizing examination and case-analysis.

Which includes

- The medical history of the patient,

- Physical and mental constitution,

- Family history,

- Presenting symptoms,

- Underlying pathology,

- Possible causative factors etc.

A miasmatic tendency (predisposition/susceptibility) also often taken into account for the treatment of chronic conditions.

What Homoeopathic doctors do?

A homeopathy doctor tries to treat more than just the presenting symptoms. The focus is usually on what caused the disease condition? Why ‘this patient’ is sick ‘this way’?

The disease diagnosis is important but in homeopathy, the cause of disease not just probed to the level of bacteria and viruses. Other factors like mental, emotional and physical stress that could predispose a person to illness also looked for. Now a days, even modern medicine also considers a large number of diseases as psychosomatic. The correct homeopathy remedy tries to correct this disease predisposition.

The focus is not on curing the disease but to cure the person who is sick, to restore the health. If a disease pathology not very advanced, homeopathy remedies do give a hope for cure but even in incurable cases, the quality of life can greatly improve with homeopathic medicines.

Homeopathic Medicines for Deliberate Self-harm:

The homeopathic remedies (medicines) given below indicate the therapeutic affinity but this is not a complete and definite guide to the homeopathy treatment of this condition. The symptoms listed against each homeopathic remedy may not be directly related to this disease because in homeopathy general symptoms and constitutional indications also taken into account for selecting a remedy, potency and repetition of dose by Homeopathic doctor.

So, here we describe homeopathic medicine only for reference and education purpose. Do not take medicines without consulting registered homeopathic doctor (BHMS or M.D. Homeopath).

Medicines for DSH:

Arsenicum album:

- Intense anxiety, restlessness, fear of being alone, perfectionism, critical of self and others, burning pains, feeling worse at night. [4]

Aurum metallicum:

- Deep depression, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, suicidal thoughts, a strong sense of duty, desire for death, especially in cases where self-harm is related to perceived failure. [5]

Belladonna:

- Impulsive behavior, violent outbursts, sudden rage, hypersensitivity to stimuli, dilated pupils, red face, throbbing headaches. [6]

Ignatia:

- Grief, disappointment, emotional turmoil, mood swings, silent suffering, sighing, lump in the throat, feeling better from distractions. [7]

Natrum muriaticum:

- Suppressed emotions, sadness, dwelling on past hurts, holding grudges, difficulty expressing feelings, desire for solitude, headaches, constipation. [8]

Staphysagria:

- Suppressed anger, resentment, humiliation, feeling taken advantage of, history of abuse, ailments from suppressed emotions, cutting pains. [9]

Hyoscyamus:

- For impulsive and destructive behavior, often accompanied by inappropriate laughter or sexual gestures.

Diet & Regimen

Diet & Regimen

There is limited research directly linking specific diets or regimens to deliberate self-harm (DSH). However, some studies suggest that certain dietary patterns and lifestyle factors may be associated with an increased risk of DSH or poorer outcomes in individuals who engage in self-harm.

Research Findings:

A study titled "Is There an Association Between Dietary Habits and Recurrent Deliberate Self-harm?" (2020) found that individuals with a history of DSH who reported eating less balanced meals were more likely to experience repeated episodes of self-harm. This suggests that a balanced diet may play a role in promoting emotional well-being and reducing the risk of DSH.

Additionally, research has shown a correlation between poor dietary habits, such as skipping meals, consuming unhealthy foods, and having a higher body mass index (BMI), with increased rates of depression and anxiety, which are known risk factors for DSH.

Possible Explanations:

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Inadequate intake of essential nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, and B vitamins has been linked to mood disorders and impaired cognitive function, potentially increasing vulnerability to DSH.

- Gut-Brain Axis: Emerging research suggests a strong connection between the gut microbiome and mental health. An unhealthy diet can disrupt the gut microbiome, potentially influencing mood and behavior.

- Blood Sugar Fluctuations: Skipping meals or consuming sugary foods can lead to rapid fluctuations in blood sugar levels, which can affect mood and energy levels, potentially triggering or exacerbating self-harming behaviors.

Recommendations:

While more research is needed to fully understand the relationship between diet and DSH, prioritizing a healthy and balanced diet is generally recommended for overall well-being and mental health. This includes:

- Eating regular meals: Avoid skipping meals and aim for three balanced meals per day.

- Choosing whole foods: Focus on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and healthy fats.

- Limiting processed foods, sugary drinks, and unhealthy fats: These can negatively impact mood and energy levels.

- Staying hydrated: Drink plenty of water throughout the day.

- Considering supplements: Talk to your doctor about whether supplements like omega-3 fatty acids or vitamin D might be beneficial.

In addition to diet, other lifestyle factors like regular exercise, adequate sleep, and stress management techniques can also play a crucial role in promoting mental health and reducing the risk of DSH.

If you or someone you know is struggling with DSH, seeking professional help is essential. A mental health professional can provide support, guidance, and treatment options to address the underlying causes and develop healthy coping mechanisms.

Do’s and Don'ts

Do’s & Don’ts of Deliberate Self-harm

Deliberate Self-harm Do’s & Don’ts

Do’s

1. Listen and Show Empathy: Be an active listener without judgment. Show understanding and empathy.

2. Encourage Professional Help: Guide them to seek help from mental health professionals, such as therapists or counselors.

3. Create a Safe Environment: Remove objects that could be used for self-harm and ensure the environment is supportive.

4. Be Supportive: Offer ongoing support and let them know you’re there for them.

5. Educate Yourself: Learn about self-harm to understand what the person might be going through.

6. Promote Healthy Coping Mechanisms: Encourage activities like exercise, art, or journaling as alternative ways to manage emotions.

7. Be Patient: Recovery from self-harm can be a long process. Be patient and provide consistent support.

Don’ts

1. Don’t Be Judgmental: Avoid criticizing or judging their behavior. This can push them away.

2. Don’t Threaten or Ultimatum: Avoid giving ultimatums or threats, as this can increase stress and worsen the situation.

3. Don’t Minimize Their Feelings: Don’t tell them to "just stop" or that their feelings aren’t valid. Acknowledge their pain.

4. Don’t Ignore Signs: Pay attention to signs of distress and take them seriously.

5. Don’t Assume It’s for Attention: Self-harm is often a coping mechanism for deeper issues. Avoid dismissing it as attention-seeking behavior.

6. Don’t Take on the Role of a Therapist: Support them, but leave the professional treatment to qualified mental health professionals.

7. Don’t Share Their Struggle Without Consent: Respect their privacy and only share information with professionals who can help.

Terminology

Terminology

Deliberate Self-Harm (DSH):

The act of intentionally injuring oneself without the explicit goal of suicide. This can take many forms, such as cutting, burning, or overdosing on medication.

Acute Medical Admissions:

Instances where a person is admitted to a hospital due to an urgent medical need, often requiring immediate treatment.

Emergency Departments:

Hospital areas dedicated to providing rapid treatment for urgent and life-threatening medical conditions.

Anxiolytics:

Medications used to treat anxiety and its associated symptoms.

Non-Opiate Analgesics:

Pain-relieving medications that do not contain opioids, such as aspirin or ibuprofen.

Salicylates:

A class of drugs that includes aspirin, often used to relieve pain and reduce inflammation.

Paracetamol (Acetaminophen):

A common over-the-counter pain reliever. While safe in recommended doses, overdoses can cause severe liver damage.

Antidepressants:

Medications used to treat depression and other mood disorders.

Tricyclics:

An older class of antidepressants that can be dangerous in overdose due to potential heart problems and seizures.

Cardiac Arrhythmias:

Irregular heartbeats that can be dangerous and potentially life-threatening.

Convulsions:

Involuntary muscle contractions (seizures).

Lacerations:

Deep cuts or tears in the skin.

Self-esteem:

A person’s overall sense of self-worth or personal value.

Impulsive Behavior:

Acting without forethought or consideration of consequences.

Unstable Moods:

Frequent and intense fluctuations in emotional state.

Disinhibition:

A lack of restraint or inhibition, often leading to impulsive behavior.

Phenothiazine:

A class of antipsychotic medications sometimes used to treat anxiety or agitation.

Psychiatric Disorder:

A mental health condition that affects a person’s thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

Personality Disorder:

A pattern of inflexible and unhealthy thoughts and behaviors that significantly impact a person’s life and relationships.

Alcohol Dependence:

A condition where a person relies on alcohol to function, experiences withdrawal symptoms without it, and has difficulty controlling their alcohol use.

Stressful Life Events:

Significant events or changes in a person’s life that cause stress and can potentially trigger mental health issues.

Couple Therapy:

A type of psychotherapy that focuses on helping couples improve their relationship and communication.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT):

A type of psychotherapy that helps people identify and change negative thought patterns and behaviors.

Child Abuse:

The physical, sexual, or emotional maltreatment of a child.

Infanticide:

The act of killing an infant.

Competence/Capacity (Legal):

A person’s legal and mental ability to make decisions about their own healthcare and life.

Informed Decision:

A decision made with a clear understanding of the relevant information and potential risks and benefits.

References

References

- Psychiatry, Fourth Edition – Oxford Medical Publications -SRG-by John Geddes, Jonathan Price, Rebecca McKnight / Ch 9.

- Deliberate self-harm in India: A systematic review" by Patel et al., published in 2012

- DSH: Self-injury, Parasuicide, and Non-suicidal Self-injury (Clinical Topics in Psychology Series) by Matthew K. Nock, Second Edition, published in 2019 by Routledge

- Leaders in Homoeopathic Therapeutics by E.B. Nash.

- Materia Medica Pura by Samuel Hahnemann.

- Kent’s Repertory of the Homoeopathic Materia Medica

- Lectures on Homoeopathic Materia Medica by J.T. Kent.

- The Soul of Remedies by Rajan Sankaran.

- Dictionary of Practical Materia Medica by J.H. Clarke.

Also Search As

Also Search As

General Search Terms:

- Self-harm

- Self-injury

- Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI)

- Cutting

- Self-mutilation

- Suicidal ideation

- Suicide prevention

- Mental health crisis

- Emotional distress

Homeopathic-Specific Search Terms:

- Homeopathic remedies for self-harm

- Homeopathy and self-injury

- Homeopathic treatment for cutting

- Homeopathy for emotional distress

- Homeopathic remedies for mental health

Additional Terms Related to the Article:

- Drug overdose as self-harm

- Risk factors for self-harm

- Prevention of self-harm

- Complications of self-harm

However, here are a few ways people might potentially access this article or similar information:

Direct Contact: If you know the author or the organization responsible for compiling the article, reaching out to them directly would be the most reliable way to obtain it. They might be able to share it privately or inform you if it’s intended for publication.

Homeopathic Channels: Since the article heavily focuses on homeopathic treatments, it’s possible it might be shared within homeopathic circles or platforms. Exploring forums, websites, or publications dedicated to homeopathy could yield results.

Similar Articles: You can search for similar articles on deliberate self-harm and homeopathy using the following keywords:

"Homeopathic remedies for self-harm"

"Homeopathy and self-injurious behavior"

"Deliberate self-harm treatment in homeopathy"

These searches might lead you to other articles or resources that discuss similar topics and treatment approaches.

Mental Health Resources: Reputable mental health organizations often provide comprehensive information on self-harm, including different treatment modalities. While they might not specifically mention homeopathy, they can offer valuable insights and guidance.

Here are a few approaches you could try:

Direct Contact:

- Author/Organization: If you know the author or organization that compiled this information, reaching out to them directly would be the most effective way to access the article.

- Homeopathic Practitioners/Organizations: Since the article heavily focuses on homeopathic treatments, contacting homeopathic practitioners or organizations in your area might help you find similar information or even this specific article if it’s being circulated within those circles.

Keyword Searches (Less Reliable):

- Exact Title: Try searching for the exact title of the article, "Deliberate Self-harm," using quotation marks ("Deliberate Self-harm"). However, this might not yield results if it’s not published online.

- Specific Phrases: Use specific phrases from the article, such as "homeopathic treatment for self-harm" or "causes of deliberate self-harm." This could lead you to similar articles or resources.

Alternative Resources:

- Homeopathic Websites/Forums: Explore websites or online forums dedicated to homeopathy. There might be discussions or articles on self-harm that contain similar information.

- Mental Health Resources: Reputable mental health organizations often provide comprehensive information on self-harm. While they might not focus on homeopathic treatments, they offer valuable insights and guidance on conventional approaches.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Deliberate Self-harm?

Deliberate self-harm is not usually fail suicide. Only about a quarter of those who have deliberately harmed themselves say they wished to die; most say the act was impulsive rather than premeditated.

What are the methods of Deliberate Self-harm?

- Drug Overdose

- The use of alcohol

- Self Injury

- Deeper lacerations,

- Jumping from heights

- Jumping in front of a either moving train or motor vehicle

- Shooting

- Drowning

- Burning

How to manage the case of Deliberate Self-harm?

- Every act assessed thoroughly

- Physical consequences of the act- hospital referral

- Psychiatric also social assessment

- All emergency department medical staff are competent to assess risk

Is deliberate self-harm the same as a suicide attempt?

No, deliberate self-harm (DSH) is not the same as a suicide attempt. While some individuals who engage in DSH may have suicidal thoughts, the majority do not intend to die. DSH is often a maladaptive coping mechanism for dealing with emotional pain or distress.

Can homeopathy help with deliberate self-harm?

While homeopathy may offer some support for individuals struggling with DSH, it’s essential to remember that it should not replace conventional mental health treatment. Consult a qualified homeopathic practitioner to discuss potential remedies and their suitability for your specific situation.

Which homeopathic remedies are commonly used for deliberate self-harm?

Homeopathic Treatment For Deliberate self-harm

Several homeopathic remedies may be considered for DSH, depending on the individual’s specific symptoms and emotional state. Some commonly used remedies include Arsenicum album for anxiety and restlessness, Natrum muriaticum for suppressed emotions, and Staphysagria for suppressed anger.

How does a homeopathic practitioner approach the treatment of deliberate self-harm?

Homeopathic treatment for DSH involves a detailed assessment of the individual’s physical, mental, and emotional state, as well as their personal history and circumstances. A personalized treatment plan is then created, incorporating constitutional remedies and specific remedies to address the underlying causes of self-harming behaviors.