Vertigo

Definition

True vertigo is characterized by a sensation of turning either of the patient or his environment, and is caused by disease of the labyrinth or its central connections.

Vertigo is a sensation of dizziness or spinning, often accompanied by nausea. While there isn’t a single perfect synonym, several words can be used to describe similar experiences:

Common Synonyms:

- Dizziness: A general term for feeling unsteady or lightheaded.

- Giddiness: A feeling of lightheadedness or whirling.

- Lightheadedness: A feeling of faintness or unsteadiness.

More Specific Synonyms:

- Disequilibrium: A loss of balance or feeling off-balance.

- Wooziness: A feeling of faintness or slight dizziness.

- Unsteadiness: A feeling of being unsteady on your feet.

Overview

Epidemiology

Causes

Types

Approach to the Patient

Risk Factors

Pathogenesis

Pathophysiology

Clinical Features

Sign & Symptoms

Clinical Examination

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Complications

Investigations

Treatment

Prevention

Homeopathic Treatment

Diet & Regimen

Do’s and Don'ts

Terminology

References

Also Search As

Overview

Overview of Vertigo:

Dizziness is an imprecise symptom used to describe a variety of sensations that include vertigo, light-headedness, faintness, and imbalance. When used to describe a sense of spinning or other motion, dizziness is designated as vertigo. Vertigo may be physiologic, occurring during or after a sustained head rotation or it may be pathologic, due to vestibular dysfunction. The term light-headedness is commonly applied to pre-syncope sensations due to brain hypo perfusion but also may refer to disequilibrium and imbalance.[2]

Epidemiology

Epidemiology Of Vertigo:

Prevalence:

- Vertigo affects approximately 20% of adults annually (BLK-Max Hospital, no year specified).

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), a specific type of vertigo, affects about 107 per 100,000 yearly in India (BLK-Max Hospital, no year specified).

- A study in 2017-2018 found the prevalence of dizziness (a broader term encompassing vertigo) among older adults (≥65 years) to be 14.6% in women and 11.6% in men (Prevalence and Associated Factors of Dizziness Among a National Community-Dwelling Sample of Older Adults in India in 2017, 2020).

Demographics:

- Age: More common in individuals above 65 years (BLK-Max Hospital, no year specified).

- Gender: Thrice more prevalent in women (BLK-Max Hospital, no year specified).

- Race: Studies suggest greater frequency in Asians, compared to Caucasians (BLK-Max Hospital, no year specified).

Specific Conditions:

Causes

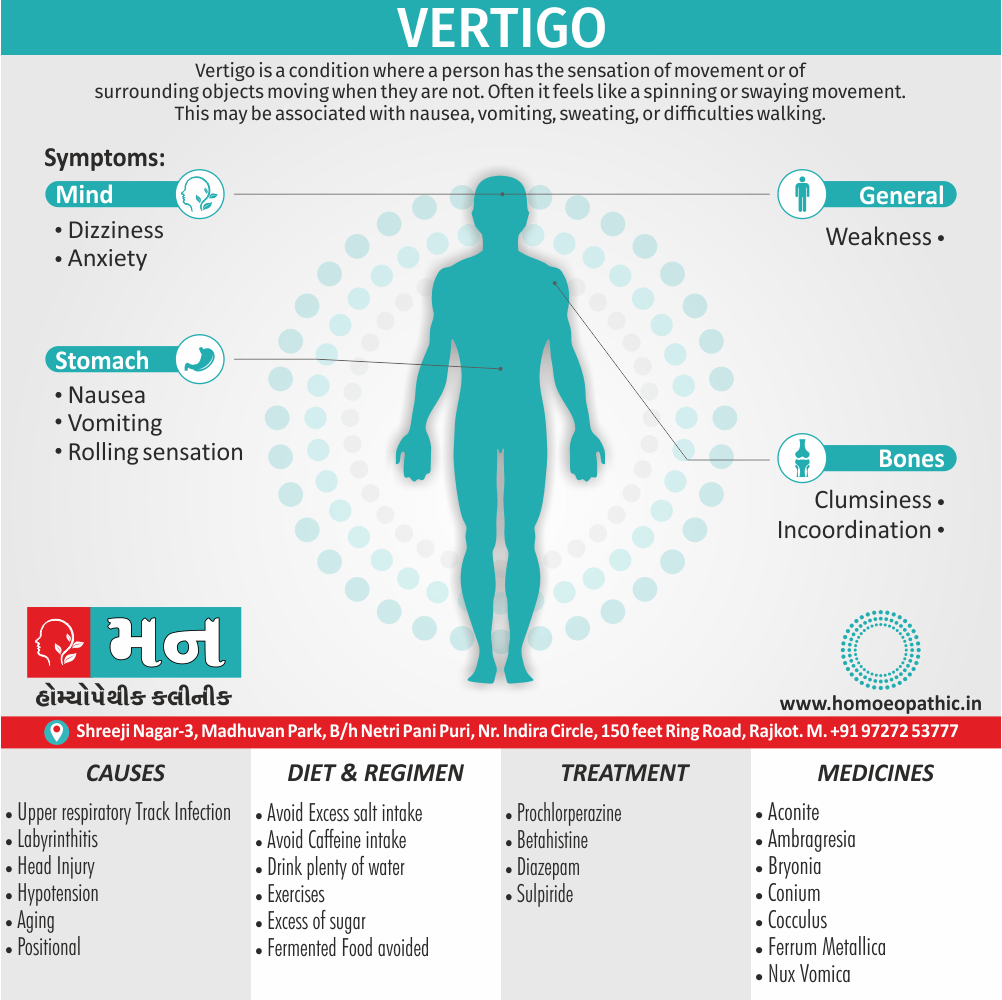

Causes of Vertigo:

- Examples of causes include:

- Pathogens: Viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites (infectious diseases)

- Genetic mutations: Inherited or spontaneous changes in genes (genetic diseases)

- Environmental factors: Toxins, radiation, nutritional deficiencies

- Lifestyle choices: Smoking, unhealthy diet, lack of exercise (contributing factors)[2]

Types

Types of Vertigo:

Classification as central and peripheral vertigo is not particularly useful since in many cases both central and peripheral systems play a role. Classification based on the pattern with which dizziness occurs i.e.:

- Sudden, serious short lasting.

- Brief dizziness spells.

- Chronic, not very severe. Persistent/protracted.

- Sudden severe gradually diminishing.

Localizing features

- Inner ear: e.g. hearing loss, tinnitus, aural fullness, otalgia or otorrhoea

- VIII nerve: facial weakness

- Cerebellopontine angle: e.g. impaired facial sensation, clumsiness, dysarthria, dysphagia, cranial nerve palsies, hemisensory loss, hemiparesis or memory disturbances

- Cerebellum: e.g. incoordination, clumsiness, dysarthria

- Cortex: Loss of consciousness, either olfactory or gustatory hallucinations.

Duration of vertigo – possible causes

- A few minutes: BPPV, vestibular epilepsy

- Several minutes to <2 hours: benign recurrent vertigo, vestibular aura of migraine

- 2 hours to <24 hours: Meniere’s disease, transient ischemic attack in the posterior circulation

- >24 hours: acute peripheral vestibular dysfunction, relapse of brainstem multiple sclerosis, bilateral vestibular failure.[1]

Approach to the Patient

HISTORY of Vertigo

When a patient presents with dizziness, the first step is to delineate more precisely the nature of the symptom. In the case of vestibular disorders, the physical symptoms depend on whether the lesion is unilateral or bilateral, and whether it is acute or chronic and progressive. Vertigo, an illusion of self or environmental motion, implies asymmetry of vestibular inputs from the two labyrinths or in their central pathways that is usually acute. Symmetric bilateral vestibular hypofunction causes imbalance but no vertigo. Because of the ambiguity in patients’ descriptions of their symptoms, diagnosis based simply on symptom characteristics is typically unreliable.

The History should focus closely on other features, including whether this is the first attack, the duration of this and any prior episodes, provoking factors, and accompanying symptoms. Dizziness Can divide into episodes that last for seconds, minutes, hours, or days.

Common Causes dizziness

Common Causes of brief dizziness (seconds) Include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) And orthostatic hypotension, both of which typically provoke by changes in head and body position. Attacks Of vestibular migraine and Ménière’s Disease often last hours. When Episodes are of intermediate duration (minutes), Transient ischemic attacks of the posterior circulation should consider, although migraine and a number of other causes are also possible.

Symptoms that accompany vertigo may helpful in distinguishing Peripheral vestibular lesions from central causes. Unilateral Hearing loss and other aural symptoms (ear pain, pressure, fullness) typically point to a peripheral cause. Because The auditory pathways quickly become bilateral upon entering the brainstem, central lesions are unlikely to cause unilateral hearing loss, unless the lesion lies near the root entry zone of the auditory nerve. Symptoms Such as double vision, numbness, and limb ataxia suggest a brainstem or cerebellar lesion.[2]

Risk Factors

Risk factors:

- Age: Vertigo becomes more common as people get older.

- Previous episodes of vertigo: Individuals who have experienced vertigo in the past are more likely to experience it again.

- Migraine: People who experience migraines have a higher risk of developing vertigo.

- Inner ear problems: Conditions such as Meniere’s disease, labyrinthitis, and vestibular neuritis can all contribute to vertigo.

- Head trauma: A head injury can damage the inner ear or the vestibular nerve, leading to vertigo.

- Certain medications: Some medications, such as those used to treat high blood pressure, depression, and anxiety, can cause vertigo as a side effect.

- Other medical conditions: Conditions such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and stroke can also increase the risk of vertigo.[7]

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis:

- Peripheral Vestibular Disorders: These encompass conditions affecting the inner ear or vestibular nerve, such as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Ménière’s disease, and vestibular neuritis.

- Central Vestibular Disorders: These involve lesions or dysfunctions within the brainstem or cerebellum, which play a crucial role in processing vestibular information. Examples include stroke, multiple sclerosis, and tumors.

- Other Contributing Factors: Vertigo can also be triggered or exacerbated by various factors, including migraines, anxiety, medication side effects, and head trauma.[8]

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology:

Peripheral Vestibular Disorders:

These disorders involve the inner ear or vestibular nerve, which transmits signals from the inner ear to the brain. Common examples include:

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV): Caused by displaced calcium carbonate crystals (otoconia) in the inner ear, triggering brief episodes of vertigo with head movement.

- Vestibular Neuritis: Inflammation of the vestibular nerve, often following a viral infection, leading to sudden, severe vertigo.

- Ménière’s Disease: Characterized by fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and episodic vertigo, thought to be due to fluid buildup in the inner ear.

- Labyrinthitis: Inflammation of the inner ear, often caused by a viral or bacterial infection, resulting in vertigo, hearing loss, and tinnitus.

Central Vestibular Disorders:

These disorders involve the brainstem or cerebellum, which process and integrate vestibular signals. Examples include:

- Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency: Reduced blood flow to the brainstem, often due to atherosclerosis, causing vertigo along with other neurological symptoms.

- Cerebellar Stroke or Tumor: Affecting the cerebellum, which coordinates balance and movement, leading to vertigo and gait instability.

- Multiple Sclerosis: Demyelination in the central nervous system can disrupt vestibular pathways, causing vertigo and other neurological symptoms.

- Migraine-Associated Vertigo: Vertigo can occur as part of a migraine attack or as an isolated symptom.

Other Causes:

Clinical Features

Clinical Feature of Vertigo:

Benign positional paroxysmal vertigo [BPPV]

Vertigo occurs when a person lies down in a particular way. The vertigo appears after a latent period of a few seconds, lasts not more than 30 seconds and quickly fades. The cause is assumed to come from debris in the endolymph of the posterior canal. Tr.- Adaptation exercises (Epley’s maneuver).

Meniere’s syndrome –

Attacks of vertigo lasting minutes or hours, accompanied by tinnitus in one ear and varying but gradually worsening hearing loss in that ear. The syndrome occurs with various internal disorders and also as an independent disorder, when it is called Meniere’s disease. Tr.- Pharmacotherapy, in severe cases surgery can be considered.

Unilateral vestibular disease syndrome

(acute vestibular vertigo) caused by sudden loss of labyrinthine function. Vertigo is severe at the onset but fades away Slowly over 2 or 4 weeks.

Hyperventilation

can cause reduced CO2 tension in the blood which can lead to cerebral ischemia. This can manifest itself in visual disturbances. Dizziness in the form of giddiness often reported. Anxiety and tachycardia. Hyperventilation can result from stress situations.

Tr.- Counselling. Advising patient to breath into a bag in front of the head in the event of an attack, and sedative medication if necessary.

Juvenile vertigo

occurs in children between ages of 4 and 14 and involves attacks lasting a few seconds or minutes during which the most pronounced symptom is anxiety. The syndrome disappears spontaneously within a few months to few years. Tr. – Low dose antiepileptic if frequency of attack is >once a week.

Aged vertigo

can occur in patient over age of 65. Cerebral Atherosclerosis plays a major role. Tr. – Pharmacotherapy, avoiding drugs which cause drowsiness.

Vestibular neuritis

mostly follows infection of upper respiratory tracts. The condition clears up within 3-6 weeks, without any persistent loss of ear function.

Migraine:

Vertigo sometimes occurs as a side effect of migraine. Specific therapy to control the vertigo is only rarely needed.[1]

Sign & Symptoms

Sign & Symptoms of Vertigo:

The hallmark of vertigo is a false sense of motion, which can manifest as:

- Spinning: A sensation that the environment or oneself is rotating

- Tilting: A feeling of being off-balance or tilted to one side

- Swaying: A sense of rocking back and forth

- Oscillopsia: An illusion of movement of the visual field

These sensations may be accompanied by other symptoms such as:

- Nausea and vomiting: Often triggered by the intense motion sensation

- Nystagmus: Involuntary eye movements, typically in a rhythmic pattern

- Imbalance and gait disturbances: Difficulty walking or maintaining balance

- Anxiety and fear: The unsettling experience of vertigo can lead to emotional distress

- Hearing loss or tinnitus: In some cases, vertigo may be associated with inner ear problems.[10]

Clinical Examination

Clinical Examination of Vertigo:

- General examination, BP, pulse, urine, blood tests.

- ENT examination: For external auditory canal, ear drums, nasopharyngeal cavity, symmetrical functioning of cranial nerves.

- Hearing test: Whispering speech. The ring of telephone is high tone stimulus.

- Tuning fork tests: The Rinne and Weber tuning fork tests serve to distinguish between a conduction defect and a perception disorder (inner ear disorder or neurosensory hearing loss).

- Postural tests: Balance tests such as Romberg’s test. The “stork” variant – standing on one leg gives more information.

- Tests for nystagmus – Gaze test: Have the patient look at point 30° away from the median line to the right and left in succession. (a) Latent nystagmus becomes stronger when looking in one direction and not dying away. Cause: Peripheral vestibular disorder. (b) Nystagmus appearing exclusively when looking to one side Unilateral gaze nystagmus. Cause – Central disorder of the nervous system. (c) Nystagmus both when looking to the right and looking to the left (symmetrical gaze nystagmus). Cause – Disorder of CNS drug abuse.

ANCILLARY TESTING

The choice of ancillary tests should be guided by the history and examination findings.

- Audiometry should be performed whenever a vestibular disorder is suspected.

- Unilateral sensorineural hearing loss supports a peripheral disorder (e.g., vestibular schwannoma).

- Predominantly low-frequency hearing loss is characteristic of Ménière’s disease.

- Electronystagmography or videonystagmography Includes recordings of spontaneous nystagmus (if present) And measurement of positional nystagmus.

Caloric Testing

Caloric Testing assesses the responses of the two horizontal semi-circular canals. The test battery often includes recording of saccades and pursuit to assess central ocular motor function. Neuroimaging is important if a central vestibular disorder is suspected. In addition, patients with unexplained unilateral hearing loss or vestibular hypofunction should undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the internal auditory canals, including administration of gadolinium, to rule out a schwannoma.[1]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Vertigo:

- Detailed History: A thorough history is essential to understand the nature of the vertigo, associated symptoms, and potential triggers. The clinician will inquire about the onset, duration, and frequency of vertigo episodes, as well as any accompanying symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, hearing loss, or tinnitus. The patient’s medical history, medications, and recent head trauma or illnesses will also be considered.

- Physical Examination: The physical examination focuses on the neurological and vestibular systems. The clinician will assess eye movements, balance, coordination, and hearing. Specific tests such as the Dix-Hallpike maneuver or the head impulse test may be performed to evaluate the function of the vestibular system.

- Diagnostic Tests: Depending on the suspected cause, additional diagnostic tests may be ordered. These may include audiometry to assess hearing, electronystagmography (ENG) or videonystagmography (VNG) to record eye movements, and imaging studies such as MRI or CT scans to rule out structural abnormalities in the brain or inner ear.[11]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis:

- Peripheral Vestibular Disorders: These include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), vestibular neuritis, labyrinthitis, Ménière’s disease, and ototoxicity.

- Central Nervous System Disorders: These include vertebrobasilar insufficiency, cerebellar infarction or hemorrhage, brainstem tumors, multiple sclerosis, and migraine-associated vertigo.[12]

Complications

Complications:

- Falls and Injuries: The imbalance and disorientation associated with vertigo can significantly increase the risk of falls, leading to fractures, sprains, and head injuries.

- Anxiety and Depression: The unpredictable nature of vertigo attacks can trigger anxiety and fear, potentially contributing to the development of anxiety disorders or depression.

- Social Isolation: Fear of experiencing vertigo in public can lead to social withdrawal and avoidance of activities, impacting social connections and overall well-being.

- Driving Difficulties: Vertigo can impair spatial awareness and reaction times, making driving dangerous.

- Motion Sickness: Individuals with a history of vertigo may become more susceptible to motion sickness, further limiting their mobility and comfort.

- Sleep Disturbances: Vertigo can disrupt sleep patterns, leading to insomnia or poor sleep quality, which can further exacerbate fatigue and other symptoms.[8]

Investigations

Investigations:

- Detailed History and Physical Examination: A thorough history, including the nature of the vertigo, associated symptoms, and any triggers, provides crucial clues. The physical examination, with a focus on the neurological and vestibular systems, helps identify any specific abnormalities.

- Videonystagmography (VNG): VNG is a sophisticated test that records eye movements to assess the vestibular system’s function. It can identify nystagmus (involuntary eye movements), which is a common sign of vestibular dysfunction.

- Caloric Testing: This test involves irrigating the ears with warm and cool water to stimulate the vestibular system and observe the resulting eye movements. It helps evaluate the function of each inner ear independently.

- Rotary Chair Testing: This test assesses the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) by rotating the patient in a controlled manner and observing their eye movements. It can help identify central or peripheral vestibular disorders.

- Imaging Studies: While not always necessary, imaging studies such as MRI or CT scans can help rule out structural abnormalities in the brain or inner ear that may be contributing to vertigo.[7]

Treatment

Treatment:

It is vestibular symptoms should be driven by the underlying diagnosis. Simply treating dizziness with vestibular suppressant medications is often not helpful and may make the symptoms worse and prolong recovery. Besides this, The diagnostic and specific treatment approaches for the most commonly encountered vestibular disorders are discussed below[2]

Management

Pharmacotherapy

(a) For symptoms of acute episode antiemetic like prochlorperazine 5 mg mouth dissolving tablet.

(b) Vestibular sedatives – Betahistine 60 mg/day, Cinnarizine 50-255 mg/day.

(c) Piracetam may be effective in older patients 400–800 Mg tds.

(d) Sulpiride 50 Mg tds.

(e) Diazepam 10–20 mg/d in combination with a drug with more specific action to reduce severity of an attack.

Adaptation methods.

BPPV in particular responds well to this treatment. Exercises –

[a.] In bed: (i) Firstly, Eye movements. Looking up and down. (ii) Secondly, Looking alternately left and right. (iii) Thirdly, Convergence exercises. (iv) Fourthly, Head movements. (v) Lastly, Bending alternately forward and backward.

[b.] Sitting: (i) Firstly, Shrugging and rotating shoulder. (ii) Secondly, Bending forwards and picking objects from the floor. (iii) Thirdly, Turning head and trunk alternately to the left and right.

[c.] Standing: (i) Changing from sitting to standing, first with eyes open, then with eyes shut. (ii) Throwing a small (ping pong) ball in an arc from hand to hand and following it with the eyes.

[d.] Walking: (i) Throwing and catching a ball while walking. (ii) Walking around the room with eyes opened and closed. (iii) Walking up and down a flight of stairs.

Surgery

This involves severing one vestibular nerve or destroying one inner ear in the case of chronic peri-labyrinthitis or a seriously disabling form of unilateral Meniere’s disease. The application of gentamycin into the middle ear in severe forms of Meniere’s disease has shown good results.

Physical therapy

Peripheral vestibular dysfunction – when vertigo continues to recur after an acute peripheral vestibular episode, the patient is described as ‘poorly compensated’. Central compensation is expedited by balance exercises.

BPPV

Particle repositioning manoeuvres (e.g. Epley) achieve a cure in up to 70% patients. Recurrent BPPV can be treated by Brandt-Daroff exercises.

Central vestibular disorders

Eye movement disorders That cause oscillopsia can be managed with low dose clonazepam or baclofen.

Cognitive behavioural therapy

Avoidance behaviour seen in patients with protracted vertigo or dizziness may require desensitization programmes by a therapist. Cognitive therapy may be required in more complex cases in which there is an inappropriate focus on the vestibular symptoms or when illness behaviour has developed.[1]

Prevention

Prevention:

- Identifying and Managing Triggers: Recognizing and avoiding situations or activities known to trigger vertigo episodes. This could include specific head movements, visual stimuli, or environmental factors.

- Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy (VRT): A specialized exercise program designed to improve balance and reduce dizziness. It helps the brain adapt to changes in the vestibular system.

- Medications: In certain cases, medication might be prescribed to manage underlying conditions contributing to vertigo or to alleviate symptoms during acute episodes.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Adopting healthy habits, such as regular exercise, stress management, and adequate sleep, can support overall well-being and potentially reduce the frequency and severity of vertigo attacks.

- Dietary Considerations: Maintaining a balanced diet and staying hydrated can help regulate blood pressure and inner ear fluid balance, which might play a role in preventing vertigo.[7]

Homeopathic Treatment

Homoeopathic Treatment :

Homeopathy treats the person as a whole. It means that homeopathic treatment focuses on the patient as a person, as well as his pathological condition. The homeopathic medicines selected after a full individualizing examination and case-analysis.

which includes

- The medical history of the patient,

- Physical and mental constitution,

- Family history,

- Presenting symptoms,

- Underlying pathology,

- Possible causative factors etc.

A miasmatic tendency (predisposition/susceptibility) also often taken into account for the treatment of chronic conditions.

What Homoeopathic doctors do?

A homeopathy doctor tries to treat more than just the presenting symptoms. The focus is usually on what caused the disease condition? Why ‘this patient’ is sick ‘this way’?.

The disease diagnosis is important but in homeopathy, the cause of disease not just probed to the level of bacteria and viruses. Other factors like mental, emotional and physical stress that could predispose a person to illness also looked for. No a days, even modern medicine also considers a large number of diseases as psychosomatic. The correct homeopathy remedy tries to correct this disease predisposition.

The focus is not on curing the disease but to cure the person who is sick, to restore the health. If a disease pathology not very advanced, homeopathy remedies do give a hope for cure but even in incurable cases, the quality of life can greatly improved with homeopathic medicines.

Homeopathic Medicines for Vertigo:

The homeopathic remedies (medicines) given below indicate the therapeutic affinity but this is not a complete and definite guide to the homeopathy treatment of this condition. The symptoms listed against each homeopathic remedy may not be directly related to this disease because in homeopathy general symptoms and constitutional indications also taken into account for selecting a remedy.

Medicines

Argentum nitricum. [Arg-n]

Vertigo, with debility and trembling, is curable by this remedy when there is much mental confusion and a sense of expansion. It seems as if houses would fall on him when he is walking through the street. It also suits vertigo from diseases of the brain and eyes.

Ambra grisea [Ambr]

Is especially useful in nervous vertigo in old people.

Aconite [Acon]

The vertigo of Aconite is hyperemic or auditory. It is worse on raising the head or rising from a recumbent position.

Bryonia [Bry]

Has a gastric vertigo with nausea and disposition to faint, worse on rising from a recumbent position and on motion.

Bromine [Brom]

Has a vertigo worse when looking at running water.[3]

Cocculus [Cocc]

Has its principal action on the solar plexus, and vertigo which is connected with digestive troubles suites this remedy, and it develops into the neurasthenic type with occipital headache and lumbo-sacral irritation. There is a flushed face and hot head, worse sitting up and riding in a carriage; it is also worse after eating.

Cinchona [Chin]

Has a gastric vertigo associated with weakness or anemia. Also, vertigo from debility, loses of fluids, etc.

Causticum [Caust]

Is suitable to vertigo preceding paralysis. There is a tendency to fall forward or sideways; there is a great anxiety and weakness in the head. It corresponds, therefore, to the vertigo and weakness in the head. It corresponds, therefore to the vertigo of organic brain diseases.

Ferrum metallicum. [Ferr]

This remedy suits anaemic vertigo, which is worse when suddenly rising from a sitting or lying position. It comes on when going downhill or on crossing water, even though the water be smooth.

Iodine [Iod]

Is also suitable for old people who suffer from chronic congestive vertigo.

Nux vomica and Pulsatilla may be needed in gastric vertigo.

Phosphorous [Phos]

says Dr. William Boericke, "displays great curative powers in every imaginable case of vertigo, especially in nervous vertigo when caused by nervous debility, sexual abuse, occurring in the morning with an empty stomach, with fainting and trembling."

Rhus toxicodendron. [Rhus-t]

This remedy suits vertigo, especially in old people, which comes on as soon as the patient rises from a sitting position. It is associated with heavy limbs is probably caused by aged changes in the brain.

Natrum salicylicum. [Nat-sal]

This remedy is especially useful in auditory nerve vertigo, and other remedies for this condition are Chininum sulphuricum, Gelsemium and Causticum.

Theridion [Ther]

Has a purely nervous vertigo, especially on closing the eyes; it is accompanied with nausea and is greatly intensified by noise or motion,[3]

Diet & Regimen

Diet And Regimen:

If you are suffering from vertigo attacks, you may try some of the food tips mentioned here after consulting your doctor.

How food affects the vestibular problems

Vertigo is a consequence of certain problems in the inner ear. It can be an infection, mechanical problems like dislodgement of calcium carbonate particles (otoliths), inflammation, functional disorders, weak immune response, increased inner ear pressure, etc.

The underlying pathological conditions need proper medication and treatment. Additionally, Dietary modifications may augment the effect of the medical management.

Foods to control vertigo

Avoid These:

If you are experiencing vertigo conditions, here is a list of foods to avoid with vertigo:

Avoid consuming fluids that have high sugar or salt content in it such as concentrated drinks and soda. These are the foods that trigger vertigo.

Caffeine intake i.e.

Caffeine is present in coffee, tea, chocolate, energy drinks and colas. It may increase the ringing sensation in the ear of the person who has vertigo issues. It has report to cause cell depolarization making the cells more easily excitable. It’s intake should regulate in patients suffering from Meniere’s disease and vestibular migraine. Caffeine strictly restrict in the vestibular migraine diet.[4]

Excess salt intake i.e.

Salt causes retention of excess fluid in the body affecting the fluid balance and pressure. High salt in the diet interferes with the internal homeostasis of the vestibular system. Additionally, Patients with Meniere’s disease and vestibular migraine ask to limit their salt intake or you may start feeling dizzy and trigger symptoms even further. Food rich in sodium like soy sauce, chips, popcorn, cheese, pickles, papad also canned foods are to be avoided. You may replace your regular salt with low sodium salt as sodium is the main culprit in aggravating vertigo.

Nicotine intake/Smoking i.e.

Nicotine is known to constrict the blood vessels. Vestibular problems arising due to vascular constriction will worsen by nicotine ingestion/smoking. In detail, Nicotine reduces blood flow to the brain and hampers in recovery by vestibular compensation.

Alcohol intake i.e.

It adversely affects the metabolism, dehydrates the body, and its metabolites are harmful to the inner ear and the brain. It may trigger severe vertigo attack, migraine, vomiting also nausea in a vertigo prone person. Alcohol may interfere with the central processing of the brain hampering vestibular compensation and affect cognitive functions negatively impacting the recovery of the patient. Besides this, It may also aggravate vertigo by altering the inner ear fluid dynamics. Wine is a known trigger of migraine attacks.

Processed food & meat are some of the foods to avoid with vertigo.

Bread and pastries can even trigger vertigo conditions.

Fried foods should be completely avoided when you go on a vertigo diet.

Pickles and fermented foods may aggravate symptoms of vertigo.

The above foods are shown to aggravate the conditions leading to vertigo. Avoiding these foods can help stabilize your condition.[4]

Include These:

Incorporate foods that are anti-inflammatory and detoxifying. They reduce the swelling of the tissue in the inner ear, repair the cells and ensure healthy cell regeneration.

Drink plenty of water and stay hydrated.

Rich in potassium; tomatoes help flush out excess fluid from the body. Include tomato in your diet, it count as the best vertigo or dizziness treatment food.

These are rich in antioxidants, micronutrients and are anti-inflammatory too. Nuts count as one of the best foods for vertigo as they are rich in vitamins. Nuts improve blood circulation in the body and inner ear, thereby reducing the inner ear pressure build-up due to excess fluid. However, in a vestibular migraine, nuts should avoid.

Ginger may ease vertigo associated symptoms, like nausea, lightheadedness and vomiting. Ginger roots are counted as the best foods for vertigo. Drinking ginger tea daily is quite effective in treating vertigo. Since ginger interferes with diabetics and blood thinning drugs, it is not advisable for these patients.

Food rich in Vitamin B & C, Zinc, Magnesium help restore nerve damage and improve blood circulation.

Foods listed here may provide relief to some people. Everybody reacts differently to different foods.

It may help to maintain a diary listing food that trigger your vertigo. Slowly you can have your personalized list of foods to counter dizziness.

Medication-induced vertigo.

If you get a vertigo bout by taking any medication, discuss it with your doctor and discontinue the drug. But before that check on safe alternate medicines so that your current health condition is not affecting. Drugs like anti-depressants, sedatives, pain-killers, muscle relaxants, anti-hypertensives, acetylsalicylic acid may cause dizziness and escalate the chances of a vertigo attack.

Importance of medical assistance cannot overlook while you are doing your best with changing food habits. Do and help yourself find a long-lasting cure for your dizziness.[4]

Do’s and Don'ts

Do’s & Don’ts :

Vertigo do’s & don’ts

Do’s:

Rest in a quiet, dark room: This can help reduce the spinning sensation and alleviate nausea.

Move slowly and carefully: Sudden movements can worsen vertigo symptoms.

Sit or lie down when you feel dizzy: This can help prevent falls and injuries.

Use a cane or walker if necessary: These assistive devices can provide stability and reduce the risk of falling.

Sleep with your head slightly elevated: This can help reduce fluid buildup in the inner ear, which can contribute to vertigo

Stay hydrated: Dehydration can worsen dizziness, so it’s important to drink plenty of fluids.

Follow your doctor’s treatment plan: This may include medications, physical therapy, or other interventions.

Don’ts:

Shouldn’t drive or operate heavy machinery: Vertigo can impair your balance and coordination, making it unsafe to drive or operate machinery.

Don’t make sudden head movements: These can trigger or worsen vertigo symptoms.

Don’t bend over or reach up high: These movements can also exacerbate vertigo.

Must Not consume alcohol or caffeine: These substances can dehydrate you and worsen dizziness.

Don’t ignore your symptoms: If you experience persistent or severe vertigo, seek medical attention.

Terminology

Terminology:

Vertigo: The primary term, referring to a false sense of motion, typically spinning or whirling. It’s crucial to differentiate this from lightheadedness or presyncope.

Dizziness: A broader term encompassing various sensations like lightheadedness, unsteadiness, or vertigo itself. It’s often used by patients but may not always indicate true vertigo.

Vestibular System: The intricate system in the inner ear and brain responsible for balance and spatial orientation. Problems here often lead to vertigo.

Nystagmus: Involuntary, rhythmic eye movements often associated with vertigo. Observing these can help diagnose the underlying cause.

Other Examples:

Otoconia: Tiny calcium crystals in the inner ear. When dislodged, they can cause BPPV.

Semicircular Canals: Fluid-filled structures in the inner ear crucial for balance.

Epley Maneuver: A specific head movement sequence to treat BPPV by repositioning the otoconia.

Tinnitus: Ringing or buzzing in the ears, sometimes accompanying vertigo.

Presyncope: A feeling of faintness or lightheadedness often preceding fainting.

Homoeopathic Terminology:

Homeopathy: The therapeutic system employed, homeopathy is based on the principle of "like cures like." It uses highly diluted substances to stimulate the body’s healing response.

Repertory: A reference book used in homeopathy, it lists symptoms and the remedies associated with them. Practitioners consult the repertory to identify potential remedies for a patient’s condition.

Materia Medica: A collection of detailed descriptions of homeopathic remedies, their properties, and the symptoms they can address. It helps practitioners understand the characteristics of each remedy.

Miasm: A fundamental concept in homeopathy, miasm refers to a predisposing disease tendency or inherited weakness. Different miasms are associated with specific types of diseases and remedies.

Other Examples:

Potency: The level of dilution of a homeopathic remedy. Higher potencies are believed to be more powerful and deeper acting.

Provings: A systematic method used in homeopathy to determine the effects of a remedy on healthy individuals. The symptoms experienced during provings are recorded and used to understand the remedy’s action.

Aggravation: A temporary worsening of symptoms after taking a homeopathic remedy, often considered a positive sign indicating the remedy is working.

Amelioration: An improvement in symptoms after taking a homeopathic remedy.

Constitutional Remedy: A remedy chosen based on the individual’s overall physical, mental, and emotional characteristics, rather than just specific symptoms.

References

Reference

- Text book of Medicine Golwala

- Harrisons_Principles_of_Internal_Medicine-_19th_Edition-_2_Volume_Set

- Therapeutics from Zomoeo Ultimate LAN

- https://www.neuroequilibrium.in/diet-to-help-you-with-your-vertigo

- Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) and risk factors for secondary BPPV: a population-based study, 2023

Prevalence and Associated Factors of Dizziness Among a National Community-Dwelling Sample of Older Adults in India in 2017,2020

Dizziness: A Case-Based Approach" (2nd Edition, 2021, published by Springer)

- Vertigo and Dizziness: A Neuro-Otological Approach" (4th Edition, 2023)

- Textbook of Clinical Neurology (3rd Edition)

- Dizziness: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 2nd Edition, by Timothy C. Hain and Stephen M. Highstein

- "Dizziness and Vertigo: Evaluation and Management" 3rd Edition.

- Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Neurology, 4e

Also Search As

Also Search As:

Online search engines:

The most common way is to use search engines like Google, Bing, or DuckDuckGo.

You can use various search terms and phrases such as:

"homeopathic article vertigo"

"homeopathy for vertigo treatment"

"homeopathic remedies for vertigo"

"vertigo homeopathic treatment research"

Specialized homeopathic websites and databases:

There are dedicated websites and databases specifically focused on homeopathy.

Some examples include:

The National Center for Homeopathy website

Homeopathy Plus

The American Institute of Homeopathy website

Academic databases:

If you’re looking for more in-depth research articles and studies, you can try searching on academic databases such as:

PubMed

Google Scholar

General search engines:

Use specific keywords: Try searches like "vertigo symptoms," "vertigo causes," "vertigo treatment," or "vertigo exercises." You can also include specific types of vertigo, such as "BPPV vertigo" or "Meniere’s disease."

Use reliable sources: Stick to reputable websites, such as medical organizations, government health agencies, and university health centers.

Medical websites and databases:

National Institutes of Health (NIH): The NIH website offers comprehensive information on various health conditions, including vertigo.

Mayo Clinic: The Mayo Clinic website provides detailed information about vertigo symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment options.

PubMed: PubMed is a database of medical literature. You can search for scientific articles about vertigo by using keywords and filters.

Image searches:

Visualize symptoms: Image searches can help you identify the specific symptoms of vertigo, such as dizziness, spinning sensation, or loss of balance.

Understand diagnostic tests: Image searches can illustrate the various tests used to diagnose vertigo, such as the Dix-Hallpike maneuver or the head thrust test.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Vertigo?

True vertigo characterized by a sensation of turning either of the patient or his environment, and cause by disease of the labyrinth or its central connections.

What causes Vertigo?

How is vertigo treated?

- Medications: to manage symptoms like nausea and vomiting.

- Vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT): to improve balance and coordination.

- Canalith repositioning maneuvers: to treat BPPV.

- Surgery: in rare cases, surgery may be necessary to correct inner ear problems.

Can vertigo be prevented?

While not all cases of vertigo can be prevented, the following measures may help reduce your risk:

What are the symptoms of Vertigo?

Can homeopathy prevent Vertigo from recurring?

Homeopathy aims to address the root cause of the vertigo, which may reduce the frequency and intensity of future episodes.

Are there any lifestyle changes that can help manage Vertigo?

Yes, certain lifestyle modifications can be beneficial. These include:

- Avoiding triggers (such as sudden head movements or bright lights)

- Getting adequate sleep

- Managing stress

- Eating a healthy diet

- Staying hydrated

Homeopathic Medicines used by Homeopathic Doctors in treatment of Vertigo?

Homeopathic Medicines

- Argentum nitricum

- Ambra grisea

- Bryonia

- Bromium

- Cocculus

- Cinchona

- Causticum

- Iodine

- Nux vomica

How long does it take to see improvement with homeopathic treatment for Vertigo?

- The response time varies depending on the individual and the severity of the condition. Some people experience relief quickly, while others may require more time.